This week’s top three summaries: R v CD, 2024 NLCA 22: self #defence force, R v Jenkins, 2024 ONCA 533: police lay #opinion, and R v Borhot, 2024 ABKB 438: reverse #closing submissions.

R v CD, 2024 NLCA 22

[June 18, 2024] Self-Defence: Measuring Force to a Nicety Not Required [Reasons by F.J. Knickle J.A. with D.E Fry C.J.N.L. and D.M. Boone J.A. concurring]

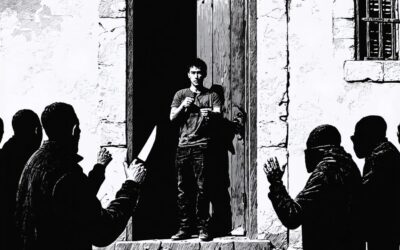

AUTHOR’S NOTE: One of the key issues that led to a successful appeal in this case was the trial judge’s failure to apply established case law, which holds that a defendant responding in self-defence does not need to measure the exact degree of force used when faced with aggression. Specifically, the principle is that individuals acting in self-defence are not expected to weigh the amount of force used with precision, especially in the heat of the moment.

Factual Background:

- The complainant had been aggressively attempting to enter a dormitory bedroom where the accused was hiding, driven by suspicion that the girl living there was seeing someone else.

- Over the course of about an hour, the complainant forcefully tried to break into the room, even applying physical force to the girl in the main room of the dorm.

- Ultimately, the complainant managed to force the door to the bedroom and lunged at the accused.

- In response, the accused repeatedly stabbed the intruder.

Key Legal Issue: Reasonable Force in Self-Defence

- Failure to Apply Self-Defence Law:

- The trial judge failed to accept that, according to established legal principles, a person defending themselves does not need to perfectly calibrate the level of force used. The law acknowledges that self-defence occurs in situations of heightened stress and fear, where the accused may not have the luxury of carefully assessing how much force is necessary.

- Reasonableness of the Accused’s Response:

- In this case, the prolonged aggression and force displayed by the complainant, including forcibly entering the bedroom and lunging at the accused, justified a significant defensive response. The case law supports the notion that the accused’s repeated use of force, including the stabbing, could be considered a reasonable reaction given the circumstances.

- Court of Appeal’s Position:

- The Court of Appeal found that the trial judge should have properly weighed the situation in light of self-defence principles. Specifically, the judge should have recognized that, given the intensity of the threat posed by the complainant, the accused’s actions could have been a lawful and proportionate response.

- The failure to instruct the jury on this key legal principle contributed to a miscarriage of justice.

Conclusion:

The appellate decision highlights that when faced with aggression, individuals are not required to “measure to a nicety” the amount of force they use to protect themselves. The accused, in this case, acted in response to prolonged and aggressive conduct, and the stabbing may well have been a reasonable defensive measure in the circumstances. The trial judge’s failure to properly apply this established legal principle justified the Court of Appeal’s decision to overturn the conviction and grant a new trial.

Copeland J.A.:

[1] The appellant was convicted in a jury trial of three counts of trafficking (cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl) and three counts of possession for the purpose of trafficking (also of cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl).

[2] The appellant raises one ground of appeal – that the trial judge erred in law by permitting the Crown to tender the lay opinions of five police officers that the appellant’s conduct observed during surveillance was, or was consistent with, drug trafficking.

[3] I would allow the appeal and order a new trial. The trial judge erred in allowing the five surveillance officers to give the impugned opinion evidence. The Crown did not seek to qualify the five officers as experts. Thus, they could not give expert opinion evidence. In any event, the form of the evidence was impermissible even had they been qualified as experts. Nor was the opinion evidence of the five officers within the scope of lay opinion evidence permitted under the principles enunciated in Graat v. The Queen, [1982] 2 S.C.R. 819. Given the prominence of the opinion evidence in the trial and the risk of misuse of improperly tendered opinion evidence in a jury trial, I would not apply the curative proviso.

Factual background

[6] In general terms, the surveillance officers described seeing the appellant drive to various locations in Barrie, including people’s homes, gas stations, parking lots, and a Tim Hortons. When the appellant arrived at a location, on some occasions an individual would enter his car and leave within a matter of minutes. On other occasions, the appellant would stop near another vehicle. At no time did any of the surveillance officers observe money, drugs, or anything else change hands.

[7] The appellant was arrested on January 20, 2017. Officers had been conducting surveillance that day. In the afternoon, the appellant arrived at an address and parked his car. He got out and entered the back seat of a black Jeep which the officers had observed several days earlier. The police followed the Jeep to another address. When the Jeep arrived at the second address, a male came out of the house and entered the back seat of the Jeep.

[8] The police then called a takedown, shortly before 5 p.m., and arrested all the occupants of the Jeep. The appellant was seated in the back seat. A woman named Yolanda Robbins was in the driver’s seat. Her boyfriend, Greg Schell, was in the front passenger seat. Ben Armstrong, the male who entered the Jeep at the second address, was also in the back seat.

[9] At the time of the appellant’s arrest, no drugs were found on his person; however, two cell phones and approximately $1,300 bundled with a rubber band were seized from him. On Mr. Schell’s person were found .29 grams of heroin/fentanyl and .48 grams of heroin/fentanyl, packaged in separate pieces of torn grocery bag.

[10] Police obtained search warrants for the appellant’s residence and his car later on January 20, 2017. While they waited for the search warrants to be issued, they conducted surveillance on the appellant’s residence….

[11] At 6:35 p.m. on January 20, the police observed the appellant’s father, Barry Jenkins, leave the residence and get into his car. Police alerted two uniformed officers to follow the car and arrest Barry. Four minutes later, the police stopped and arrested Barry. The police searched Barry’s car. In the car, on the floor below the driver’s seat, they found a large black cannister. On later analysis, the contents of the cannister were three baggies of cocaine weighing a total of 20.5 grams and three baggies of a mixture of heroin/fentanyl/caffeine weighing a total of 22.7 grams. The cannister was not tested for fingerprints.

[12] Barry was called as a witness at trial. He testified that he found the cannister on the stairs to the basement and that he had never seen it before. He said that after hearing about the appellant’s arrest, he was on his way to the police station to surrender the cannister. However, he did not provide the officers with the cannister as soon as he was pulled over. Rather, the officers found it when they searched the car.

[16] The appellant testified. He denied any knowledge of the cannister. He said it was not his and the drugs in it were not his. He denied he was involved in trafficking drugs. He testified that the mask, respirator, and cash were related to his freelance autobody repair work. He denied knowledge of the scale.

The trial judge erred in law by admitting the impugned opinion evidence of the five surveillance officers

[17] The trial judge erred in allowing the Crown to lead opinion evidence from five surveillance officers that the appellant’s conduct they observed during surveillance was, or was consistent with, drug trafficking. In particular, he erred in finding that it was admissible as lay opinion evidence.

[18] I reach this conclusion for the same reasons as in this court’s recent decision in R. v. Nguyen, 2023 ONCA 531, 429 C.C.C. (3d) 192, at paras. 48-54. The surveillance officers’ evidence should have been limited to their factual observations during the surveillance.

(i) The impugned opinion evidence

[19] I will not summarize the opinion evidence of all of the five surveillance officers. The substance was the same for all five. Repeatedly, during the course of examinations-in-chief, after each officer explained a particular factual observation of the appellant during surveillance, Crown counsel then asked a question to the effect of: What did you make of this observation, in your experience? I extract excerpts from the evidence of three surveillance officers to provide the flavour of the impugned opinion evidence.

Examination-in-chief of DC Anthony Forrest

Q. Okay. So let me ask you about that first observation you made; the individual coming out of the home, getting into the vehicle, and getting out. You – you said you’ve been a member of the police – Barrie Police since 2008?

A. That’s correct.

Q. Have you had experience with surveilling individuals?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. What – what do you make of this in your experience?

A. This sort of short trip like, the person’s inside for three minutes. This sort of short meet is very consistent with a drug transaction. It’s also very consistent for drug dealers and buyers to conduct their business in vehicles where they’re afforded some concealment. It’s very common.

(ii) This court’s decision in Nguyen

[20] In Nguyen, this court considered the same type of evidence from an officer who was not qualified as an expert to give opinion evidence. After giving evidence about surveillance observations of Mr. Nguyen, the officer testified that in his opinion what he had observed – one male picking up or dropping property off to another male – was “consistent with drug-related activity.”

[21] This court held that the trial judge in Nguyen erred in admitting the officer’s opinion evidence. The Court started with the well-established proposition that opinion evidence is presumptively inadmissible: Nguyen at para. 48, citing R. v. D.(D.), 2000 SCC 43, [2000] 2 S.C.R. 275, at para. 49. The opinion evidence was improperly admitted in Nguyen because it did not satisfy the admissibility requirements for either expert opinion evidence or lay opinion evidence.

[22] In relation to expert opinion evidence, there were two problems in Nguyen. First, the Crown had not established the officer’s expertise to offer the opinion he provided. Second, the opinion provided by the officer did not meet the necessity requirement for admissibility of expert evidence. The opinion that the conduct of picking up or dropping off property between two people “was consistent with drugrelated activity” was not a matter that non-experts – a trier of fact – are unlikely to form a correct judgment about: see also R. v. Gill, 2017 ONSC 3558, at paras. 41- 44, per Fairburn J., as she then was.

23] This court further held that the officer’s opinion evidence – that the conduct observed was consistent with drug trafficking – did not fall within the scope of lay opinion evidence: Nguyen, at para. 53. Lay opinion evidence is admissible where a witness is “merely giving a compendious statement of facts that are too subtle or complicated to narrate separately and distinctly”: Graat, at p. 841. Where a surveillance officer gives evidence about their observations of a suspect (properly admissible), they can relate the evidence of the factual observations they made without providing the further opinion evidence that the conduct observed is consistent with drug trafficking: see also Gill, at paras 43-44.

(iii) Application to this appeal

[24] In this case, on a voir dire that occurred after the officers testified, the trial judge held that the opinion evidence of the five surveillance officers that what they observed the appellant do during the surveillance was, or was consistent with, drug trafficking was admissible as lay opinion evidence.

[25] This was an error. The evidence of the five surveillance officers should have been limited to their observations of the appellant during the surveillance (and of the people he was with, to the extent it was relevant).

[27] First, the Crown did not seek to qualify the five surveillance officers as experts on the indicia of drug trafficking.

[28] Second, the conclusory opinion evidence given by each of the five officers was not necessary for the jury to form a correct judgment about the evidence. The jury was capable of assessing the factual observations described by the officers. In particular, the jury was capable of weighing the shortness of the appellant’s interactions with third parties as a factor that may, in the context of the evidence as a whole, be probative of drug trafficking transactions.

[29] Third, the conclusory opinion that the conduct observed was, or was consistent with, drug trafficking was not within the scope of lay opinion evidence. The jury could understand, and the officers could convey, the factual observations of the appellant’s conduct during the surveillance without the further opinion that the officers believed that the conduct was, or was consistent with, drug trafficking.

[30] To be clear, I am not suggesting that expert opinion evidence could not be led on the issue of indicia of trafficking if a trial judge was satisfied that it met the White Burgess admissibility criteria: White Burgess Langille Inman v. Abbott and Haliburton Co., 2015 SCC 23, [2015] 2 S.C.R. 182. This court and the Supreme Court have recognized that expert opinion evidence may be tendered on issues related to drug trafficking, such as “chains of distribution, distribution routes, means of transportation, methods of concealment, packaging, value, cost and profit margins”, where the evidence is based on specialized knowledge outside the knowledge of a lay trier of fact: R. v. Sekhon, 2014 SCC 15, [2014] 1 S.C.R. 272, at para. 18; Nguyen, at para. 52.

[31] I would also emphasize that where opinion evidence is tendered on issues related to drug trafficking, it must be limited to providing the jury with evidence in general terms about the area of expertise (for example, drug pricing; trafficking quantities; methods of drug trafficking), which they may consider and, if they accept it, apply as part of their fact finding to decide what inferences or conclusions to draw from other evidence (for example, surveillance evidence). Expert opinion may not extend to conclusions or inferences to be drawn about the accused’s conduct….

[32] Indeed, in this trial the Crown did lead expert opinion evidence about indicia of drug trafficking. As noted above, the trial judge qualified DC Ford as an expert on this issue. The appellant does not challenge that ruling or the scope of DC Ford’s evidence. However, DC Ford’s opinion evidence about indicia of drug trafficking was properly limited to providing a list of indicia of drug trafficking, rather than a conclusory opinion that the appellant’s conduct as observed during the surveillance was, or was consistent with, drug trafficking.

[34] The defence raised objection to the admissibility of the opinion evidence of the surveillance officers in an application brought after the completion of the evidence and prior to the closing addresses. The defence argued that the impugned evidence from the five officers was opinion evidence and was inadmissible. Defence counsel at trial acknowledged that he should have objected to the opinion evidence from the five surveillance officers at the time it was tendered.

[35] I am not persuaded that this is a case where the late objection by the defence should lead the court to conclude either that there was no prejudice from the impugned evidence or that the defence made a tactical decision not to object earlier.

[37] I acknowledge that the trial judge was placed in a difficult position by the late objection by the defence. But that did not relieve him of his gatekeeping responsibility to ensure that opinion evidence only be admitted if it fell within a proper exception for either expert or lay opinion: Nguyen, at para. 54. The trial judge failed to exercise his gatekeeping function at the time the opinion evidence was tendered.

[38] It may be that had the trial judge given the jury a clear, sharp instruction to disregard the impugned opinion evidence of the five surveillance officers and to only consider the factual evidence of their observations, this could have addressed the prejudice: Sekhon, at para. 48. Unfortunately, the trial judge did not take that route. Rather, he held that the opinion evidence from the surveillance officers was admissible as lay opinion evidence. This was an error.

[39] For these reasons, I conclude that the trial judge erred in admitting the opinion evidence of the five surveillance officers that their observations of the appellant during surveillance were, or were consistent with, drug trafficking. Their evidence should have been limited to their factual observations during surveillance.

The Crown has not met its burden for the curative proviso to be applied

[45] First, unlike Sekhon and Nguyen this appeal is from a jury trial. The risk of misuse of improperly admitted evidence is greater in a jury trial because jurors are not legally trained: Sekhon, at para. 46; R. v. Lewis, 2012 ONCA 388, 284 C.C.C. (3d) 423, at paras. 22, 28.

[46] Thus, for the purpose of considering the application of the curative proviso, this case is more like Lewis, which was a jury trial, than Sekhon and Nguyen. In Lewis, this court emphasized, at paras. 22 and 28, the risk in a jury trial that a jury will give undue weight to improperly admitted opinion evidence. In this case, as in Lewis, the Crown phrased its questions in eliciting the impugned evidence in a manner that also elicited the experience of the officers in drug investigation surveillance. This had the effect of emphasizing the purported expertise of the officers without actually having them qualified as experts.

[48] Further, the improperly admitted opinion evidence was given prominence in the Crown’s address to the jury. Repeatedly in her closing address, when Crown counsel (not Ms. Carley) described the various surveillance observations of the officers, she concluded the description with: “Police believe this to be a drug transaction.”

[50] These factors distinguish this appeal from Sekhon and Nguyen. In both of those appeals, the appellate court found the improperly admitted evidence was a small part of the trial. I do not reach the same conclusion in this appeal.

Disposition

[60] I would allow the appeal, set aside the convictions, and order a new trial.