This week’s top three summaries: R v Ordonio, 2025 ONCA 135: s.8 #voluntariness & time, R v Deverze, self #defence and weapon and R v Hallman, 2025 ONCA 123: #provocation

R v Ordonio, 2025 ONCA 135

[February 25, 2025] Voluntariness: Length of the Interrogation and the Reid Technique [Reasons by David Brown J.A. with Janet Simmons and L. Favreau JJ.A concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The Reid Technique has been widely litigated in criminal cases, and while this decision did not explicitly add it to the common law confessions rule, it provides a persuasive analysis of its problematic nature. The case offers a roadmap for defence lawyers to identify and label coercive interrogation tactics, which in itself forces courts to scrutinize police conduct more carefully.

A key takeaway from this case is the Court of Appeal’s clarification on voluntariness. The trial judge incorrectly focused on linking problematic police tactics to an immediate visible breakdown by the accused. However, the Court of Appeal emphasized that voluntariness is assessed by the cumulative effect of police conduct—even if hours pass between coercive tactics and the confession, the earlier misconduct can still render the statement involuntary. This ruling strengthens the defence’s ability to challenge confessions obtained through psychologically manipulative interrogations.

I. OVERVIEW

[1] In early 2019, the appellant, Justine Ordonio, was tried before a judge and jury and convicted on one count of first degree murder for his involvement in the April 2015 stabbing death of Teresa Hsin.

[3] Central to the Crown’s case was a statement given by the appellant to the police during a 13-hour interview on November 10 and 11, 2015 (the “Statement”). On the voir dire regarding the admissibility of the Statement, the Crown conceded that absent the Statement there was insufficient remaining evidence to proceed against the appellant: 2019 ONSC 1804, at para. 6.

[5] I conclude that the trial judge erred in her analysis that resulted in the admission of the appellant’s Statement. I would allow the appeal, set aside the conviction, direct a new trial, and remit the issue of the Statement’s admissibility to the judge who presides at a new trial. Given that disposition, it is not necessary to address the other grounds of appeal.

[7] As part of their investigation of the killing of Ms. Hsin, the police conducted an interview of the appellant at 14 Division in Toronto on July 10, 2015. During that interview, the appellant denied any knowledge of or involvement in Ms. Hsin’s killing.

[8] On November 10, 2015, at 12:30 p.m., the appellant was arrested for first degree murder at his Toronto home. During the drive to a Peel Regional Police station, the appellant was cautioned and advised of his right to counsel. He was then asked whether the police had made “a mistake” by arresting him. The appellant denied any responsibility for the crime and responded to some other questions posed by the arresting officers during the drive. The Crown conceded that by failing to hold off questioning until the appellant had spoken to counsel, the police had breached the appellant’s rights under s. 10(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

[9] When the appellant arrived at the police station at 1:17 p.m., he was taken directly into an interview room. At 1:35 p.m., Detective Mark Heyes entered the interview room and began to talk with the appellant. Det. Heyes made a telephone available to the appellant, who spoke with a lawyer for just under 10 minutes. That conversation ended at 2:13 p.m. Det. Heyes re-entered the room and began to question the appellant. The interview continued until approximately 2:00 a.m. the following morning, November 11, 2015.

[10] During that time there were some breaks in the interview: to obtain water and cigarettes for the appellant; to enable bathroom breaks; to bring in a Swiss Chalet dinner; and some periods when Det. Heyes simply left the room.

[11] Towards the end of the interview, the appellant wrote and signed the Statement regarding his involvement in the death of Ms. Hsin. Parts of the Statement were inculpatory, though they did not exactly correspond to the Crown theory of the case.

[13] At the preliminary hearing of the three accused, the appellant contended that his Statement was the product of Det. Heyes’s use of an interrogation method known as the Reid Technique. He argued that the use of such a technique of interrogation should act as a material reason to find that the Statement was not voluntary…

IV. THE PRINCIPLES GOVERNING THE ADMISSION OF A CONFESSION

[25] The common law confessions rule provides that any statement of the accused to a person in authority, which affords relevant and material evidence in respect of its maker, the accused, is inadmissible at the instance of the Crown unless the Crown proves on a voir dire, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the statement was voluntary: Matthew Gourlay et al., Modern Criminal Evidence (Toronto: Emond, 2022), at p. 419; David Watt, Watt’s Manual of Criminal Evidence (Toronto: Thomson Reuters, 2023), at §37.04. As put by the authors of Sopinka, Lederman & Bryant: The Law of Evidence in Canada, 6th Ed., 4 at §8.71: “Reduced to its essentials, the voluntariness inquiry focuses predominantly, though not exclusively, on the ability of the accused to make a meaningful choice whether or not to confess” (footnotes omitted).

[29] Tessier, at para. 68, contains a succinct summary of the factors usually considered in a voluntariness inquiry:

The law relating to the modern confessions rule in Canada is settled. A confession will not be admissible if it is made under circumstances that raise a reasonable doubt as to voluntariness. The Crown bears the persuasive or legal burden of proving voluntariness beyond a reasonable doubt. The inquiry is to be contextual and fact-specific, requiring a trial judge to weigh the relevant factors of the particular case. It involves consideration of “the making of threats or promises, oppression, the operating mind doctrine and police trickery”. These factors are not a checklist: ultimately, a trial judge must determine, based on the whole context of the case, whether the statements made by an accused were reliable and whether the conduct of the state served in any way to unfairly deprive the accused of their free choice to speak to a person in authority. [Citations omitted; emphasis added.]

[31] Regarding the factor of oppression, Watt notes that there is no exhaustive list of what acts or omissions of a police interviewer might create an oppressive atmosphere, but he writes that there can be no doubt that “[a]mongst the many factors that can create an atmosphere of oppression are (i) depriving D [the defendant] of food, clothing, water, sleep or medical attention; (ii) denying D access to counsel; (iii) excessively aggressive, intimidating questioning over a long time; and (iv) the use of nonexistent evidence”: Watt, at §34.07; see also Tessier, at para. 99.

[34] To summarize, the confessions rule jurisprudence makes two key points. First, the rule seeks to protect against false confessions. Second, the rule directs courts to inquire into all the circumstances surrounding the making of a confession and red-flags, for a court’s consideration, a wide variety of circumstances traditionally grouped under the categories of inducements, oppression, operating mind, and police trickery.

V. THE REID TECHNIQUE OF QUESTIONING

A. The criminology literature

[35] The Reid Technique of questioning forms one part of what the criminology literature describes as the broader Reid Method. The method was developed by John Reid and others in the 1940s as an interview and interrogation technique designed to evaluate the veracity of a suspect without the use of mechanical aids, such as the polygraph. The Reid Method has three stages: (i) the pre-interview factual analysis of a case; (ii) a behavioural analysis interview of a suspect; and (iii) the interrogation of the suspect, which the literature calls the Reid Technique.

[36] The first two stages of the Reid Method are described by Nadia Klein in “Forensic Psychology and the Reid Technique of Interrogation: How an Innocent Can Be Psychologically Coerced into Confession” (2016) 63:4 Crim LQ 504, as follows at pp. 506-508:

The first stage of the Reid technique is a factual analysis of the particular case. Before any interviews or interrogations take place, an investigator should become thoroughly familiar with the known facts and circumstances of the case, as it would not be possible to conduct an effective interview or interrogation without this knowledge.

The second stage is the Behavioural Analysis Interview (BAI), and is the result of Reid and [Frank] Inbau’s considerable work on conducting polygraph interviews. In his work, Reid observed “that truthful suspects appeared to display different attitudes and behaviours during their polygraph examinations than deceptive suspects.” Reid meticulously documented these behaviours over several years and developed categories of ‘behaviour symptoms’ that seemed to be a reliable indicator of truth or deception. This led to the creation of ‘behaviour provoking questions,’ questions that an innocent suspect tended to answer differently from a guilty suspect. These questions became the foundation of the BAI.

Using the guidelines outlined by Reid, by the end of the BAI the investigator should be “definitely or reasonably certain” as to the guilt of the suspect. For those suspects that are deemed truthful this is where the process ends. For those found to be deceptive, the investigator moves into the final stage, the interrogation. [Footnotes omitted.]

[37] The method’s second stage – the behavioural analysis interview – has attracted much critical comment in the literature, which calls into question the assertion that interrogators can accurately identify those who are lying during the BAI phase of the interview:…

[38] The third and final stage of the Reid Method involves the interrogation technique that the jurisprudence calls the “Reid Technique”. A conceptual summary of the Reid Technique was provided by Kozinski at pp. 311-312:

According to the authors of the Reid Manual, “only people who are believed to be guilty are … interrogated.” This means that, by the time police get to this stage in the process, they are no longer engaged in the objective collection of information. Instead, their single-minded objective is to get the suspect to admit his guilt and sign a confession that is rich in detail and other indicia of voluntariness and genuineness. While the Reid Manual describes this part of the Technique as a nine-step process, it actually resolves itself into three major components: (1) tell the suspect you already know for sure he committed the crime, and cut off any attempts on his part to deny it; (2) offer the suspect more than one scenario for how he committed the crime, and suggest that his conduct was likely the least culpable, perhaps even morally justifiable (minimization); (3) overstate the strength of the evidence the police have inculpating the suspect – by inventing non-existent physical evidence or witness statements, for example – and assuring him he’ll get convicted regardless of whether he talks. The driving idea is to persuade the suspect that it’s in his best interest to give a confession that paints him in a positive light.

[39] As Kozinski mentions, the literature usually breaks the Reid Technique down into nine steps. An exhibit marked in the proceedings below set out the nine steps of a Reid Technique interrogation:

The Reid technique’s nine steps of interrogation are:

1. Direct confrontation. Advise the suspect that the evidence has led the police to the individual as a suspect. Offer the person an early opportunity to explain why the offense took place.

2. Try to shift the blame away from the suspect to some other person or set of circumstances that prompted the suspect to commit the crime. That is, develop themes containing reasons that will psychologically justify or excuse the crime. Themes may be developed or changed to find one to which the accused is most responsive.

3. Try to minimize the frequency of suspect denials.

4. At this point, the accused will often give a reason why he or she did not or could not commit the crime. Try to use this to move towards the acknowledgement of what they did.

5. Reinforce sincerity to ensure that the suspect is receptive.

6. The suspect will become quieter and listen. Move the theme of the discussion towards offering alternatives. If the suspect cries at this point, infer guilt.

7. Pose the “alternative question”, giving two choices for what happened; one more socially acceptable than the other. The suspect is expected to choose the easier option but whichever alternative the suspect chooses, guilt is admitted. As stated above, there is always a third option which is to maintain that they did not commit the crime.

8. Lead the suspect to repeat the admission of guilt in front of witnesses and develop corroborating information to establish the validity of the confession.

9. Document the suspect’s admission or confession and have him or her prepare a recorded statement (audio, video or written)

[40] Klein argues that before an interrogation using the Reid Technique starts, the investigator has decided the suspect is guilty and the purpose of the interrogation is to elicit a confession. However, she notes that the “curators of the Reid technique adamantly deny this fact and state that their interrogation method is designed to elicit the truth from a suspect, not a confession”: at p. 508. [Emphasis by PJM]

[42] Klein offers her assessment of the psychological goals the Reid interrogation process seeks to achieve, stating at p. 513:

The Reid technique construes interrogation as the psychological undoing of deception. It is a two-stage process. The first stage, encompassing steps one through four of the nine-step interrogation, is designed to reduce the suspect’s self-confidence in surviving the interrogation by convincing them that there exists incontrovertible evidence of their guilt, that no reasonable person could come to any other conclusion, and that there is no way out of their situation other than to confess. Once the suspect has accepted that they are powerless to change their situation, the investigator moves to the second stage, steps five through nine, wherein inducements are offered, by way of alternate reasons for the crime, that are designed to persuade the suspect that confessing is in their best interest psychologically, materially, and legally. [Footnotes omitted.]

[43] Klein continues, at p. 514:

According to Reid, the suspect will confess when the perceived consequences of the confession are more desirable then [sic] the internal struggle of lying. Therefore, the goal of a Reid interrogation “is to decrease the suspect’s perception of the consequences at confessing, while at the same time increasing the suspect’s internal anxiety associated with [their] deception.” [Footnotes omitted.]

[45] The literature suggests that not all nine steps need be used during a particular Reid Technique interrogation: Chapman, at p. 386. However, the materials filed before us on this appeal do not disclose any consensus on which or how many of the nine steps must be used by a police questioner before the interrogation can be classified as one that uses the Reid Technique.

[47] These two points – the lack of consensus on the elements necessary for an interview to qualify as a Reid Technique interrogation and the sharing of some tactics by both the Reid and non-Reid techniques of questioning – are important points to which I will return in my analysis in Part VII.B below.

[51] In Barges, in ruling that the post-arrest interview was inadmissible, the court stated, at para. 96:

The length of the interview, the sometimes aggressive stance used, the repeated assertions by the accused that he does not wish to answer or speak to the police, and the persistent reference to the themes that it is only fair to his family for him to advance his side of the story, and, more importantly, that failure on his part to do so will lead to the police putting forth a picture that he is a monster and a slaughterer, and the suggestions by the interviewers that if he wishes to give his explanation, now is the time and that he may not have any further opportunity to do so all leave me with a reasonable doubt as to whether this statement has been proven to be voluntary. A fair reading of the interview supports the inference that cooperation by Mr. Young may deflect what otherwise will be the painting of a planned and deliberate murder involving him. Although he does [not] succumb in the sense of any directly inculpatory admissions, those utterances he does make which the Crown views as useful flow from the atmosphere created within the interview. [Emphasis added.]

[53] Ontario jurisprudence consistently has held that police use of the Reid Technique, or elements thereof, does not in itself render a statement inadmissible. However, the case law instructs that a court must look at all the circumstances of a Reid Technique interrogation, together with their cumulative effect, to determine whether the Crown had discharged its burden to establish voluntariness beyond a reasonable doubt.

[62] To date, most Ontario cases have adopted the following approach to a voluntariness inquiry where it is alleged the Reid Technique of questioning has been used:

In the words of Morgan and Smith, at para. 26, “[t]he fundamental question is not what technique the police officer used but rather, considering all the circumstances of the police questioning and statements given by the accused, whether the statement was voluntarily given.… [I]t is not the court’s role to evaluate the utility of the Reid Technique but to adjudicate on the admissibility of the end product” (citations omitted);

“The issue is whether the use of the [Reid] technique in the particular circumstances of the individual case will leave the trier with a reasonable doubt as to voluntariness”: Jorgge, at para. 32;

“[T]he onus is on the Crown to prove voluntariness beyond a reasonable doubt and that all of the circumstances are to be viewed cumulatively in deciding whether this onus has been met.… [The] main concern in the circumstances of this interview flows from a consideration of the end result of the interview seen as a whole”: Barges, at paras. 82, 84 (emphasis added).

B. Analysis

[74] …under the current rule, all confessions are presumed inadmissible regardless of the mode of police questioning, and in all cases the Crown must demonstrate the voluntariness of the statement, otherwise it is not admitted into evidence. It strikes me that the gloss or amendment proposed by the appellant and CLA posits a distinction that does not amount to a real practical difference.

Is the current confessions rule not achieving its stated objective?

[76] Second, I am not persuaded that the record before us demonstrates that the existing confessions rule is failing to achieve its objective of preventing the admission of false confessions when the statements were elicited by police use of the Reid Technique, or any other technique for that matter

[80] Moving beyond the case law, the only article from the criminology literature filed on this appeal that attempted to provide a broad, empirically grounded, picture of the effect or impact of different questioning techniques was that by Christian A. Meissner et al., “Accusatorial and information-gathering interrogation methods and their effects on true and false confessions: a meta-analytic review” (2014) 10:4 J of Experimental Criminology 459. This meta-review of the criminology literature from 1967 through 2013 classified police questioning techniques as either “information-gathering” (employing open-ended, exploratory approaches and direct, positive confrontation) or “accusatorial” (psychologically-based methods that use close-ended or confirmatory questions)…

…they cautioned that the field studies could not distinguish between true and false confessions because “ground truth” in such a real-world context was nearly impossible to determine.

[82] …They reported that in laboratory studies accusatorial methods significantly increased the likelihood of obtaining a false confession whereas information-gathering approaches appeared to show a numerical decrease in the rate of false confessions obtained relative to accusatorial methods. The authors acknowledged that those findings were not particularly robust due to the small number of studies eligible for the meta-review.

[83] While this meta-review seems to confirm the common sense intuition that a period of accusatorial questioning by a person in authority may well increase the likelihood of a false statement as compared to questioning using more open-ended, information-gathering approaches, the study did not examine the effectiveness of evidentiary rules used by various jurisdictions to screen for that risk…

[89] Given those features, injecting into a confession voir dire a threshold issue of whether the police used the Reid Technique, or a technique that substantially tracked the nine steps of the Reid Technique, or some hybrid of the Reid Technique and another technique, would create an issue that would consume more judicial resources without any apparent forensic benefit as compared to the application of the existing confessions rule. That is because at the end of the day, as stated in Beaver, the current confessions rule provides that any confession to a person in authority is presumptively inadmissible unless the Crown proves the voluntariness of the statement beyond a reasonable doubt.

VIII. SECOND ISSUE: DID THE TRIAL JUDGE ERR IN ADMITTING THE APPELLANT’S STATEMENT?

[92] I am persuaded by the appellant’s submission that the trial judge erred in her analysis that resulted in her ruling the appellant’s Statement to be voluntary. In my view, the trial judge’s analysis that the Statement was voluntary was marked by two errors: (i) the trial judge failed to consider the circumstances of the interview as a whole and assess the cumulative effect or impact of the 13-hour interrogation on the Statement’s voluntariness; and (ii) the trial judge made a palpable and overriding error of fact in finding that the appellant did not fall asleep during the interrogation.18

The trial judge’s failure to consider the circumstances of the interview as a whole

[95] The jurisprudence on the confessions rule stresses that when considering whether a statement was made voluntarily, a court must consider all of the circumstances surrounding the making of the statement. And, indeed, the trial judge recognized that a confession analysis must consider all relevant factors, both in regard to police conduct and to its effect on a suspect’s ability to exercise his free will: at paras. 75-76. However, in my view the trial judge erred in her application of that principle.

[96] Oickle identified “excessively aggressive, intimidating questioning for a prolonged period of time” as one factor that can create an atmosphere of oppression: at para. 60. The present case certainly involved questioning for a prolonged period of time – almost 13 hours – and the video records numerous instances of aggressive questioning, many prolonged. In such circumstances, the assessment of the voluntariness of the Statement necessarily required the trial judge to examine the cumulative impact of prolonged, aggressive questioning. In my respectful view, the trial judge failed to do so in the present case.

[98] After providing an overview of the interrogation, and the relevant legal principles, the trial judge conducted her voluntariness analysis by first assessing how the appellant presented himself during the interview – she concluded that he was “a cunning, calculating individual who held his own throughout” – and then examining the conduct of Det. Heyes under the headings of “Oppression” and “Inducements”.

[99] Although the trial judge conducted an extensive review of police conduct under those headings, overall she took a “piecemeal” rather than a cumulative approach to assessing the effect or impact of specific police conduct. She limited her assessment of the impact to specific points of time and then gauged the lapse of time between the conduct and the appellant making admissions. Her reasons disclose several examples of this temporally-limited analytical approach:

The appellant had complained about the cold temperature in the interrogation room and there was a lapse of time before the police provided warmer clothing. Food was not given to the appellant until close to 7:00 p.m., some six hours after his arrest and transport to the police station. Though the trial judge found the delay in providing the appellant with warmer clothing “somewhat disturbing”, at para. 90, she concluded that since more than two hours elapsed between getting the warmer clothing and dinner and the start of the appellant’s admissions, “[t]his suggests there is no causal connection between those factors and the admissions ultimately elicited from Ordonio”: at para. 91;

As part of his effort to develop a rapport with the appellant, Det. Heyes lied about the circumstances surrounding his son’s death. The trial judge recognized that the police officer did so “undoubtedly to encourage Ordonio to follow the same example as the ‘offender’ who obtained forgiveness by admitting to his crime.” The trial judge concluded that Det. Heyes’s lie “did not work” since the appellant “remained insistent that he played no role in this crime until hours later, when the full weight of the evidence impacted him”: at para. 113. This was one reason that led the trial judge to conclude that “there is no causal connection between Heyes’ use of any aspects of the Reid method and the admissions ultimately elicited from Ordonio”: at para. 114; and

Around 6:00 p.m., the appellant asks Det. Heyes, “[h]ypothetically how, how much am I looking at?” A lengthy back and forth ensued, in which Det. Heyes stated that he could not tell the appellant for sure because he was not a judge. Defence counsel submitted that by suggesting to the appellant that he might get a lower prison sentence if he “comes forward” and explains “the circumstances”, the police officer offered an improper inducement that contributed to the appellant’s subsequent admissions. The trial judge did not accept that submission for several reasons, one of which, at para. 132, was that

[N]othing flows from this exchange. It is not until approximately 9:00 p.m. – three hours later – that Ordonio begins to reveal anything meaningful about his involvement, and that was triggered by various pieces of damning evidence that Heyes confronted him with.

[100] These portions of her reasons suggest the trial judge approached her examination of police conduct on the basis that unless a particular instance of police conduct occurred close in time to when the appellant started to make his admissions, the conduct could not have affected the voluntariness of the appellant’s Statement. Certainly, there has to be some connection between the police conduct and a confession: Oickle, at para. 84. But to render a statement involuntary an Oickle factor need not be the sole contributing factor: R. v. Othman, 2018 ONCA 1073, 144 O.R. (3d) 37, at para. 24, citing Oickle, at para. 57. [PJM Emphasis]

[102] …The obligation of a court to consider the effect of the circumstances of the interrogation as a whole requires a court to assess, especially during a lengthy interrogation, whether the cumulative effect or impact of police interrogative conduct rendered the statement involuntary…

[103] …the portions of the trial judge’s reasons set out at para. 99 above lead me to conclude that she lost sight of that obligation – she was more concerned about the lapse of time between troubling or disturbing police conduct and when the appellant started making admissions than the cumulative impact of the conduct during prolonged, aggressive questioning. With all due respect to a very experienced trial judge, I am not satisfied that her one-sentence assessment of the cumulative effect of police interrogation conduct was sufficient to satisfy her duty to assess the overall impact on voluntariness of all the circumstances surrounding the making of the Statement, especially when the interrogation went on for 13 hours, was marked by very aggressive police questioning and some police lies, and, as discussed below, drew an acknowledgement on cross-examination by the police interrogator that the appellant had fallen asleep during the interview.

Whether the appellant fell asleep during the interrogation

[104] The videotape of the 13-hour interrogation shows the appellant periodically resting his head on a table and, at one point, lying on the floor for an extended period of time after Det. Heyes had left the room.

[108] While there was no evidence from the appellant on the point since he did not testify at the voir dire, there was evidence before the trial judge from the other person in the interrogation room, Det. Heyes.

[109] In his evidence, Det. Heyes acknowledged that there were times during the 13-hour interview when he found the appellant had fallen asleep and, on reflection, perhaps he should not have awakened the appellant but let him sleep…

[111] As well, it was an error of fact on a very material point that affected the trial judge’s assessment of the facts: Oickle, at para. 71. As recognized by Oickle, depriving the person questioned of sleep can create an atmosphere of oppression that leads to false confessions: at paras. 58-60.25 Indeed, the trial judge recognized this very risk in her ruling on the application to admit expert evidence concerning the association between interviewing techniques and false confessions: 2019 ONSC 3017. In rejecting the appellant’s application, the trial judge wrote at para. 12:

The main concerns about the interview in this case involve its length; the aggressive and leading style of questioning; and the physical conditions throughout, such as fatigue, hunger and discomfort. To the extent those concerns exist, they do not require an “expert” to identify them. That is particularly so where, as here, the entire interview was audio and videotaped. Jurors can evaluate whether questions are manipulative or suggestive. They can see when someone is being bullied or badgered. They know that hunger and exhaustion do not bring out reliable answers. In other words, human experience and common sense will suffice. And to the extent they need direction on this, the court can and should provide it. [Emphasis added.]

[113] Accordingly, I conclude that in light of the evidence of Det. Heyes and the jurisprudence regarding depriving a suspect of sleep during an interrogation, the trial judge made a palpable and overriding error of fact in finding that the appellant did not fall asleep during the 13-hour interrogation.

IX. CONCLUSION AND DISPOSITION

[114] For the reasons set out above, I conclude that the trial judge’s ruling that the Statement was voluntary was tainted by error. In those circumstances, I would allow the appeal, set aside the conviction, direct a new trial, and remit the issue of the Statement’s admissibility to the judge who presides at a new trial. Given that disposition, it is not necessary to address the other grounds of appeal advanced by the appellant.

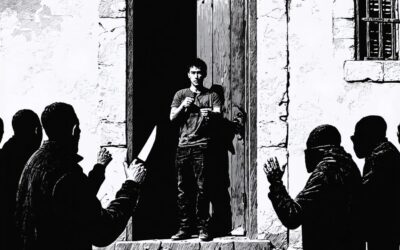

R v Deverze, 2025 ABCA 71

[February 28, 2025] Self-Defence: Unlawful Activity Does not Prohibit Reliance on this Defence [Ritu Khullar C.J.A., Dawn Pentelechuk, and Alice Woolley JJ.A.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This case was decided in favor of the defence due to the trial judge’s failure to provide sufficient reasons for rejecting self-defence. However, the most significant aspect of the ruling is the Court’s clear statement that an accused’s involvement in unlawful activity does not automatically make an otherwise reasonable act of self-defence unreasonable.

Practically, this means that individuals engaged in illegal activities—such as drug dealers—can still claim self-defence if they face an unprovoked violent attack. This ruling reinforces that self-defence is judged on the circumstances of the attack itself, not the accused’s unrelated criminal activity. It’s a valuable precedent for defence lawyers handling self-defence cases involving clients with criminal backgrounds.

The Court:

[1] On March 22, 2020, the occupants of a silver Dodge Journey minivan opened fire on the car being driven by the appellant Samuel Deverze after it had stopped in an alley, breaking his rear side window. The appellant carried an unlicensed nine-millimetre semi-automatic Glock 17 handgun which he explained was for protection due to threats he’d received after an altercation in Montreal some months earlier. After the shots were fired, the appellant jumped out of the car. The appellant testified he was unsure of where the shots were coming from, so he ran to the front of the car, using it as a shield. From there he fired at the minivan.

[2] CCTV footage shows the minivan slowly reversing down the alley, with shots apparently being fired out the passenger side window. After reversing some way, the minivan accelerates quickly towards the appellant before turning into a parking lot.

[3] After the minivan had turned into the parking lot, the appellant ran forward, stopped in a shooting stance and fired several shots at the driver’s side of the minivan. The appellant ran out of bullets and returned to his vehicle, which would not start. He departed on foot and hid in a nearby apartment building until he was apprehended by police. In the meantime, the minivan drove away

[5] On July 31, 2023, the trial judge convicted the appellant of five offences related to possession, storage and handling of a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, pointing a firearm at another person, and careless use of a firearm: R v Deverze, 2023 ABCJ 175 [Trial Decision]. The appellant had conceded at trial that the evidence established that he committed the offences of unsafely storing a firearm and possessing a firearm for which he did not hold a license: Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, ss. 86(2) and 91(1). He argued, however, that he ought not to be convicted of the remaining offences on the basis of self-defence: Criminal Code, s. 34. The trial judge rejected that position, finding that the appellant “changed from victim to aggressor during the incident”, so that his purpose was no longer defensive as required by s. 34(1)(b), and his response was not reasonable as required by s. 34(1)(c): Trial Decision at paras 63-64.

[7] For reasons to be sufficient they must, when read in light of the record as a whole, “explain what the trial judge decided and why they decided that way in a manner that permits effective appellate review”: R v GF, 2021 SCC 20 at para 69; R v Sheppard, 2002 SCC 26 at paras 46, 55.

[8] The trial judge’s reasons in this case needed to explain why he concluded that the Crown had proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the appellant did not act in self-defence. Section 34(1) of the Criminal Code establishes the three requirements for self-defence, “usefully… conceptualized as (1) the catalyst; (2) the motive; and (3) the response”: R v Khill, 2021 SCC 37 at para 51 [Khill]…

[11] Unfortunately, particularly when assessed in light of the trial record, the trial judge’s reasons do not explain how he resolved the legal and factual issues raised by the Crown’s case and the appellant’s claim of self-defence.

[12] As noted, the trial judge rejected self-defence by concluding that “the actions of the accused in response to the threat or use of force being used against him changed from victim to aggressor during the incident”, such that the appellant did not have a defensive purpose and did not act reasonably: Trial Decision at paras 63-64. The trial judge supported this conclusion by further finding that “a reasonable person in a comparable situation would have immediately left the scene, either in his vehicle or on foot” and that “individuals who carry handguns in public who are not licensed to do so do not in my opinion fall within the definition of a “reasonable” person, as contemplated by Parliament or the Supreme Court of Canada”: Trial Decision at paras 68-69.

[14] To start, the trial judge collapsed the analysis of the appellant’s purpose under s 34(1)(b) which is a subjective inquiry focused on “personal purpose”, with the analysis of the reasonableness of the appellant’s response under s 34(1)(c) which is an objective inquiry, taking into account the circumstances of the appellant but not what he “thought at the time”.Khillat paras 59, 64-65… [Emphasis by PJM]

[19] The trial judge also did not address or evidently consider the possibility that, even if the appellant had an aggressive purpose, he also continued to have a defensive one: R v Jeremschuk, 2024 ABCA 268 at paras 27-30.

[20] In short, there is nothing in the reasons to show the appellant or the public how or why the trial judge decided there was no reasonable doubt the appellant’s purpose stopped being defensive, or to permit this Court to review the legal and factual sufficiency of that conclusion: R v SAS, 2023 ABCA 236 at para 62.

[21] The trial judge’s explanation for his conclusion that the appellant’s response was not reasonable, as required by s. 34(1)(c), is equally deficient. Most importantly, the trial judge did not review the relevant factors from s. 34(2). In Khill, the Supreme Court explained that through s. 34(2), “Parliament has … expressly structured how a decision maker ought to determine whether an act of self-defence was reasonable in the circumstances”: Khill at para 64. A decision-maker must consider every factor in s. 34(2) that is relevant to the circumstances of the case before them: Hodgson at para 76.

[25] To support his determination that the appellant did not act reasonably, the trial judge said that a reasonable person would have left the altercation: Trial Decision at para 68. He did not explain why he reached that conclusion. Moreover, s. 34(2)(b) and s. 34(2)(g) make the existence of other possible responses one factor in assessing the proportionality and reasonableness of the appellant’s response to the threat, but do not make the existence of alternatives determinative. They must be included in the analysis with the other relevant factors in s. 34(2). Here, a finding that he could have run away is relevant to the assessment of the reasonableness of the appellant’s response, but must be considered alongside the extreme and unexpected nature of the threat the appellant faced, the absence of evidence to suggest he provoked the attack, and the speed at which the events unfolded: R v Robertson, 2020 SKCA 8 at paras 54-55; R v Desmond, 2024 NSSC 60 at para 373; R v Jobe, 2021 ONSC 7508 at paras 121-122; R v Tag El Din, 2019 ABQB 317 at para 39. As the Supreme Court noted in Hodgson at para 78(g), “A person in a threatening situation need not carefully assess the threat and thoughtfully determine the appropriate response”: see also, R v Cunha, 2016 ONCA 491 at paras 7, 9. [Emphasis by PJM]

[26] The trial judge suggested that the appellant’s unlawful possession of a handgun made his response unreasonable. An individual’s voluntary proximity to circumstances involving violence and firearms may be relevant to the assessment of whether their conduct was reasonable for the purposes of s. 34(1)(c). On the appropriate facts it falls within the scope of s. 34(2) as a “relevant circumstance” related to that person and their actions. As the Supreme Court observed in Khill at para 56, reasonableness is not considered from the perspective of “members of criminal subcultures”. A claim of self-defence also does not insulate a person from the criminal consequences of unlawful conduct associated with possession and storage of a firearm, as illustrated here by the appellant’s uncontested conviction for the offences of unsafely storing a firearm and possessing a firearm for which he did not have a license.

[27] Nonetheless, the mere fact of unlawful activity does not preclude reliance on self-defence; illegality does not inherently render an otherwise reasonable response to an unprovoked violent attack unreasonable: R v Sparks-MacKinnon, 2022 ONCA 617 at para 17. On the facts of this case in particular, the appellant’s illegal activity was with respect to his possession and storage of the firearm. The illegality of the appellant’s possession and storage of the handgun has no obvious probative value with respect to the reasonableness of his use of it in the circumstances. Not having a handgun would have affected the appellant’s response, but it is not evident how having and storing the handgun legally would have made a difference, either to the likelihood of the altercation occurring or to how he responded to it. It is not relevant to the assessment here. [Emphasis by PJM]

[28] The appeal must thus be allowed. The trial judge did not sufficiently explain the grounds for rejecting the claim of self-defence and the explanation he did provide suggests that he made reviewable errors in assessing whether the appellant acted in self-defence.

[33] The matter of the three charges for which the appeal was allowed are returned to the Alberta Court of Justice on March 13, 2025 at 9:00am in Courtroom 305 at 601 5th Street SW Calgary, Alberta to schedule a new trial.

R v Hallman, 2025 ONCA 123

[February 21, 2025] Provocation and Response to Jury Questions [Reasons by R. Pomerance J.A. with Grant Huscroft and J. Dawe JJ.A. concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In provocation cases, the term “sudden” appears in two key aspects of jury instructions:

- The rapidity of the provoking conduct.

- The speed of the accused’s response.

In this case, the jury asked specific questions about these concepts, but instead of providing a tailored explanation, the trial judge merely referred them back to the written instructions. Additionally, the judge misdirected the jury by suggesting that the suddenness of the provoking conduct should be assessed in relation to all interactions between the accused and the deceased. However, the Court clarified that while the broader context of the exchanges is relevant, only the specific provocative act must be sudden—not the entire interaction. This error contributed to the appeal decision.

[1] The appellant was convicted of the second-degree murder of Nicholas Baltzis. Mr. Baltzis died during a physical altercation between the two men at his residence. At trial, the appellant maintained that he acted in self-defence, but relied in the alternative on the partial defence of provocation. The trial judge instructed the jury on both defences.

[2] During their deliberations, the jury asked several questions about the provocation defence. The appellant argues that the trial judge’s answers to these questions were either non-responsive, potentially unclear, or incorrect. I agree with this submission…

A. FACTUAL BACKGROUND

(1) The altercation

[3] The appellant and Mr. Baltzis had known each other for some time. On the day of the fatal altercation, the appellant went to the house where Mr. Baltzis was staying to help him clear it out. They both consumed alcohol and drugs, and at one point they posted a “selfie” photograph on social media showing them standing side-by-side together, both smiling.

(2) The appellant’s statement to police

[5] At trial, the appellant relied on the content of his statement to police, which was put in evidence by the Crown. He explained that as the day progressed Mr. Baltzis “kept looking at me saying stupid stuff and asking me what my name was”, which made no sense because they had known each other for four years. The appellant described Mr. Baltzis’s words as “all mumble jumble”. He told the police that Mr. Baltzis “just kept getting rowdier and rowdier with me, to the point where he eventually just grabbed a knife and like held it to my throat”.

[6] The appellant said that when Mr. Baltzis put the knife to his throat, he “just lost it”. They fought over the knife and they both ended up on the floor. The appellant said that he punched Mr. Baltzis in the head and managed to wrestle the knife away, suffering a deep cut to his hand in the process. The appellant then stabbed the knife into Mr. Baltzis’s shoulder and bicep area, and continued to stab him, estimating that he stabbed Mr. Baltzis around 20 times. He then moved Mr. Baltzis’s body and began beating him with various objects, including a golf club and a cane.

(3) The deceased’s injuries

[7] The deceased suffered extensive injuries. His immediate cause of death was blood loss from 19 stab wounds to his chest, abdomen, face, and extremities. The stab wounds penetrated both of Mr. Baltzis’s lungs, his heart, his liver, and his eye. Mr. Baltzis also had a broken nose, multiple head injuries, and a perforation of the skull, but a forensic pathologist testified that these other injuries did not contribute his death.

C. THE JURY’S QUESTIONS ON PROVOCATION AND THE TRIAL JUDGE’S ANSWERS

(1) The jury’s questions on provocation

(a) Questions on the first day of deliberations

[13] During their first day of deliberations, the jury sent some questions to the trial judge, two of which are pertinent to the appeal 2. First, they asked: “[i]s it possible to receive a transcript of the judge’s instructions of the law provided this morning. We understood we would receive it, but we only have the decision tree sheets. Thank you.” The trial judge responded to this question by providing a single copy of the charge to the jury, telling the jurors they could have additional copies if they requested them.

[14] The jury’s second question was: “For provocation, does there only need to be one “no” and does that specific “no” need to be unanimous? *Need more clarification on provocation decision tree.*”

[15] The trial judge declined to answer this question. Instead, she told the jury that they might find the answer in the written charge, but she did not identify any particular passage…

(b) Questions on the second day of deliberations

[17] The next day, the jury asked a further series of questions about provocation, which referred to the provocation decision tree

We are stuck on provocation …

Some jurors are interpreting wording differently, for example:

what does “sudden” and “suddenly” mean from points 4 and 5

what is “sufficient” (pt #2)

[20] After a lengthy discussion with counsel, the trial judge provided her answers to these questions, reproduced below. The jury then resumed deliberating and returned a verdict of guilty of second-degree murder about four hours later.

[21] The trial judge divided the jury’s questions into four parts, which she read out and answered as follows:

The first question I am going to deal with … which I have labelled number one is, “We are stuck on provocation. Some jurors are interpreting wording differently. For example, what does ‘sudden’ and ‘suddenly’ mean from points four and five? Is ‘sudden’ the specific moment, the indictable conduct, or would it encompass the whole event and circumstances?”

That is the first part. So, this is what I am going to say to you in response. ‘Sudden’ and/or ‘suddenly’ means this, “Provoking conduct or words that strikes upon a person’s mind, unexpectedly, when he or she is not prepared for it.” Okay?

The second portion of that, “Is ‘sudden’ a specific moment, the indictable conduct, or would it encompass the whole event and circumstances?”

So, the indictable conduct we have spoken about is the Assault with a Weapon allegation, and no, it is not confined to just that. You take into account everything that was said, or done, at the time, including any previous exchanges that may have occurred between them. [PJM Emphasis]

And then your last question on this is, “What is meant by ‘sufficient’?”

“Sufficient” means, “Whether an ordinary person, in these circumstances, with the characteristics of Mr. Hallman, confronted with the same wrongful act or insult, would have lost the power of self-control.” And then what I have marked as question two, “When looking at the decision tree for provocation, is the conduct referred to in the boxes on the left-hand side only referring to the indictable conduct described in the top box, or does conduct in the subsequent boxes refer to the totality of the conduct of Mr. Baltzis?” And again, you should consider all of the evidence, and everything that was said and/or done, not just what we referred to as the Assault with the Weapon.

D. ANALYSIS

[22] Jury questions offer a narrow sightline into the jury room during deliberations. They signal that that the jury, or some jury members, need help to properly discharge their oaths or affirmations. Jury questions are a delicate matter, calling for care and caution. When a jury question discloses confusion or uncertainty on a particular point, that confusion and/or uncertainty must be addressed in a direct and timely way, failing which the validity of the verdict may be cast into doubt. Questions from a jury “merit a full, careful and correct response” by the trial judge: R. v. W.(D.), [1991] 1 S.C.R. 742, at pp. 759-60.

[24] For its part, this court recently echoed the importance of a clear answer to a jury’s cry for help. “A question from a jury usually concerns an important point in the jury’s reasoning, identifying an issue on which they require direction”. It indicates “a particular problem the jury is confronting – on which they are focused”, so “courts have recognized that answers to jury questions will be given special emphasis by jurors”. That means trial judges must “fully and properly answer a question posed by the jury … even if the subject-matter of the question has been reviewed in the main charge”: R. v. Shaw, 2024 ONCA 119, 170 O.R. (3d) 161, at para. 64.

[26] The defence of provocation hinged on the notion of suddenness. However, the jury could only apply that criterion if the jurors knew what had to be “sudden”. As the appellant points out, the CJC model instructions use the term “sudden” to describe two different things: (i) the rapidity of the provoking conduct by the deceased (point 4); and (ii) the speed of the accused’s response to that conduct (point 5). The jury specifically asked for guidance about both points. [Emphasis by PJM]

[27] The trial judge’s answer to the jury’s questions were deficient in three main respects.

[28] First, while the trial judge did address what the term “sudden” meant in the context of the fourth element of the provocation defence, her answer essentially repeated what she had already said about this element in her main charge. Since the jury already had a written copy of the charge and was seeking additional guidance from the trial judge, simply repeating what she had said already was unlikely to be of any real assistance. In this situation, “[e]xplaining the idea the jury has asked to have clarified in different words may be what is necessary for the jury to understand”: R. v. Layton, 2009 SCC 36, [2009] 2 S.C.R. 540, at para. 25

[29] Second, the trial judge’s answer addressed the meaning of “sudden” only in the context of the fourth element. The definition of “sudden” from her main charge that she repeated in her answer was meaningless in relation to the fifth element, which asked whether the appellant had acted suddenly, before there was time for his passion to cool. The question of what it meant for the appellant to act suddenly was never clarified for the jury.

[31] Third, and most importantly, the trial judge’s answers about what aspect of Mr. Baltzis’s conduct had to be sudden amounted to misdirection.

[32] It is true that the jury had to consider the encounter as a whole in determining whether the provocative act by Mr. Baltzis was sudden. However, the encounter as a whole was not what had to be sudden. It simply provided the context for considering the suddenness of the provocative act, which in this case was the appellant’s claim that Mr. Baltzis had held a knife to his throat.

[33] The jury was evidently confused about this critical point, and wanted guidance about which aspect of Mr. Baltzis’s “conduct” had to be “sudden”: was it his act of placing the knife to the appellant’s neck, or the “totality of [his] conduct” leading up to the fight in which he was killed?

[34] The trial judge’s answers did not clarify the essential point. Rather than telling the jury that what had to be “sudden” was the deceased’s provocative act of holding a knife to the appellant’s throat, the trial judge told them that the suddenness requirement was not “confined to just that”, and that they had to “take into account everything that was said, or done … including any previous exchanges that may have occurred between them.” Although the second part of this answer was correct in one sense – the jury did have to “take into account everything” as context – the jury might well have misunderstood that the defence would fail if the overall encounter between Mr. Baltzis and the appellant was not “sudden”. [Emphasis by PJM]

[35] The potential for misunderstanding was compounded by the final portion of the trial judge’s answer, in which she directed the jurors that the “conduct” of Mr. Baltzis they were to consider was as “everything that was said and/or done, not just what we referred to as the Assault with the Weapon”. Although it was not incorrect that the jury had to “consider” all of this conduct, the jury could very well have been left with the mistaken impression that the requirement of suddenness applied to the whole of the encounter, and globally, to all of Mr. Baltzis’s alleged erratic conduct. This had the potential to doom the defence to failure. [Emphasis by PJM]

[36] It was open to the jury to be left with a reasonable doubt about whether Mr. Baltzis’s alleged use of the knife represented an escalation of aggression that the appellant was not expecting, even though on the appellant’s account it occurred against the backdrop of other erratic behaviour by Mr. Baltzis that day. On the other hand, the jury was unlikely to conclude that the entire course of erratic behaviour qualified as “sudden”, because on the appellant’s account it went on for at least an hour. If the jury was satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that the “suddenness” requirement in the fourth element of the defence was not satisfied, the defence of provocation could not succeed.

[37] In all of the circumstances, the jury was not adequately instructed on one of the defences relied upon by the appellant at trial. Having found an air of reality to the defence of provocation, the trial judge was obliged to ensure that the jury was properly instructed, not only in the main charge, but also in responses to the jury’s questions…

[38] For all of these reasons, I would allow the appeal order a new trial.