This week’s top three summaries: R v Bykovets, 2024 SCC 6: #privacy & IPs, R v Gill, 2024 BCCA 63: #overseizure, and R v Slapkauskas, 2024 ONCA 154: PTC for #hospital stay.

Our firm focuses on representation in complex criminal trials and criminal appeals. We also provide ghostwriting services to other firms for written submissions. Consider us for your appeal referrals or when you need written submissions on a file.

Our lawyers have been litigating criminal trials and appeals for over 16 years in courtrooms throughout Canada. We can be of assistance to your practice. Whether you are looking for an appeal referral or some help with a complex written argument, our firm may be able to help. Our firm provides the following services available to other lawyers for referrals or contract work:

- Criminal Appeals

- Complex Criminal Litigation

- Ghostwriting Criminal Legal Briefs

Please review the rest of the website to see if our services are right for you.

R v Bykovets, 2024 SCC 6

[March 1, 2024] S.8 Charter – Reasonable Expectation of Privacy [Majority Reasons by Karakatsanis J. with Martin, Kasirer, Jamal and Moreau JJ. concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The normative exercise of adjudicating whether a reasonable expectation of privacy exists for s.8 Charter purposes remains confusing for lower courts with judges often declining to follow the authority of Cole, Marakah, and Reeves in favour of American-style interpretations involving assessments of whether the person gave up privacy to non-state actors. This analysis is wrong and has, yet again, been put to bed by the majority in this case. The second part of this case is the recognition that IP addresses should be private as against the state. For the most part people are forced to share this information and do so unintentionally with various corporate actors as they access the internet with various devices. The only way to live modern life without sharing this information is live as a digital recluse. The Court has reinforced that Canadians do not have to do so to maintain privacy with respect to the state.

I. Introduction

[3] This appeal asks whether an IP address itself attracts a reasonable expectation of privacy. The answer must be yes.

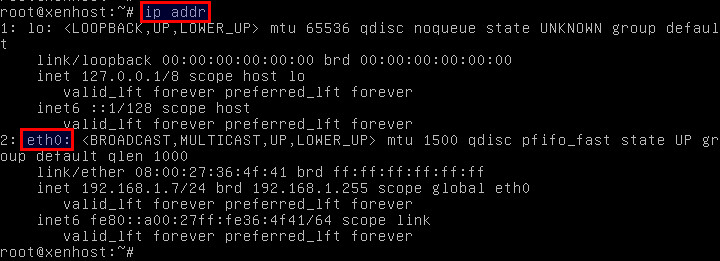

[4] An IP address is a unique identification number. IP addresses identify Internet-connected activity and enable the transfer of information from one source to another. They are necessary to access the Internet. An IP address identifies the source of every online activity and connects that activity (through a modem) to a specific location. And an Internet Service Provider (ISP) keeps track of the subscriber information that attaches to each IP address.

[6]….We have never approached privacy piecemeal, based on police’s stated intention to use the information they gather in only one way. The right against unreasonable search and seizure, like all Charter rights, must receive a broad and purposive interpretation, reflective of its constitutional source. Since Hunter v. Southam Inc., [1984] 2 S.C.R. 145, we have held that s. 8 seeks to prevent breaches of privacy, rather than to condemn or condone breaches based on the state’s ultimate use of that information. Privacy, once breached, cannot be restored.

[7] To that end, our Court has applied a normative standard to reasonable expectations of privacy. We have defined s. 8 in terms of what privacy should be — in a free, democratic, and open society — balancing the individual’s right to be left alone against the community’s insistence on protection. This normative standard demands we take a broad, functional approach to the subject matter of the search and that we focus on its potential to reveal personal or biographical core information (R. v. Marakah, 2017 SCC 59, [2017] 2 S.C.R. 608, at para. 32).

[9] Casting the subject matter of this search as an abstract string of numbers used solely to obtain a Spencer warrant goes against these precedents. IP addresses are not just meaningless numbers. Rather, as the link that connects Internet activity to a specific location, IP addresses may betray deeply personal information — including the identity of the device’s user — without ever triggering a warrant requirement. The specific online activity associated with the state’s search can itself tend to reveal highly private information. Correlated with other online information associated with that IP address, such as that volunteered by private companies or otherwise collected by the state, an IP address can reveal a range of highly personal online activity. And when associated with the profiles created and maintained by private third parties, the privacy risks associated with IP addresses rise exponentially. The information collected, aggregated and analyzed by these third parties lets them catalogue our most intimate biographical information. Viewed normatively and in context, an IP address is the first digital breadcrumb that can lead the state on the trail of an individual’s Internet activity. It may betray personal information long before a Spencer warrant is sought.

[10] And the Internet has concentrated this mass of information with private third parties operating beyond the Charter’s reach. In this way, the Internet has fundamentally altered the topography of informational privacy under the Charter by introducing third-party mediators between the individual and the state — mediators that are not themselves subject to the Charter. Private corporations respond to frequent requests by law enforcement and can volunteer all activity associated with the requested IP address. Private corporate citizens can volunteer granular profiles of an individual user’s Internet activity over days, weeks, or months without ever coming under the aegis of the Charter. This information can strike at the heart of a user’s biographical core and can ultimately be linked back to a user’s identity, with or without a Spencer warrant. It is a deeply intrusive invasion of privacy.

[11]…. A production order for an IP address would require little additional information to what police must already provide for a Spencer warrant. Both society’s interest in effective law enforcement and its interest in protecting the informational privacy rights of all Canadians must be respected and balanced.

[12] On balance, the burden imposed on the state by recognizing a reasonable expectation of privacy in IP addresses is not onerous. This recognition adds another step to criminal investigations by requiring that the state show grounds to intrude on privacy online. But in the age of telewarrants, this hurdle is easily overcome where the police seek the IP address in the investigation of a criminal offence. Section 8 protection would let police pursue the Internet activity related to their law enforcement goals while barring them from freely seeking the IP address associated with online activity not related to the investigation. Judicial oversight would also remove the decision of whether to reveal information — and how much to reveal — from private corporations and return it to the purview of the Charter.

II. Background

[15] The appellant, Andrei Bykovets, was convicted of 14 offences for using unauthorized credit card data to buy gift cards online, using those gift cards to make purchases in store, and possessing material related to credit card fraud.

[16] During the Calgary Police Service’s investigation into fraudulent online purchases from a liquor store, police learned that the store’s online sales were managed by Moneris, a third-party payment processing company. Police contacted Moneris to obtain the IP addresses used for the transactions, and Moneris voluntarily identified two. Police then obtained a production order compelling the addresses’ ISP to disclose the subscriber information — the name and address of the customer — for each IP address, as required by Spencer. One was registered to the appellant, the other to his father.

[17] Police then used this subscriber information to seek and execute search warrants for the residential addresses of the appellant and his father. The appellant was arrested, convicted after a trial, and his convictions were confirmed on appeal.

[19] Defence counsel submitted a forensic investigator’s expert report providing a technical summary of IP addresses and their functions. The report showed that there are internal and external IP addresses. External IP addresses are used to transfer information across the Internet from one source to another through a modem rented from the ISP. An external IP address is much like the street address of an individual’s house. Without one, a user can neither send nor receive data. A modem or router also assigns an internal IP address to each device on a local network, roughly equivalent to the individual rooms in a house.

[20] IP addresses can also be static or dynamic. Most are dynamic, meaning that the ISP can change a user’s external IP address without notice and for any number of reasons. ISPs keep a record of which subscriber each external IP address was assigned to and for what time period.

[21] A user’s ISP can be determined by entering their IP address into an IP lookup website. The police can then request subscriber information for the assigned IP address from the ISP, as contemplated by Spencer. That said, the expert explained that one may still take steps to determine a user’s identity, without resorting to an ISP, through the information logged on the website of a third-party company. Third-party companies, such as Google or Facebook, can track the external IP addresses of each user who visits their site and log this information to varying degrees. These companies can determine the identity of those individual users based on their Internet activity on their sites (expert report, reproduced in A.R., at p. 311). The effect is compounded when information from multiple sites is collected (p. 312).

[22] Thus, in the expert’s view, if those seeking to identify a particular Internet user have access to information logged by third-party companies, “it is not necessary to obtain ISP-held subscriber information in order to accurately identify a particular internet user” (p. 312).

IV. Analysis

[28] This appeal raises a single issue: Does a reasonable expectation of privacy attach to an IP address? In my view, the answer is yes. As I will explain, an IP address is the crucial link between an Internet user and their online activity. Thus, the subject matter of this search was the information these IP addresses could reveal about specific Internet users including, ultimately, their identity. To find that s. 8 does not extend to an IP address because police collected it only to obtain a Spencer warrant ignores the information it can reveal without a warrant. Such an analysis reflects piecemeal reasoning based on how the state intends to use the information in a specific case, contrary to the broad, purposive approach required by s. 8’s constitutional status. Nor can the analysis be limited to the privacy interests affected by what the IP address can reveal on its own, without consideration of what it can reveal in combination with other available information, particularly from third-party websites. Viewed normatively, an IP address is the key to unlocking a user’s Internet activity and, ultimately, their identity, such that it attracts a reasonable expectation of privacy. If s. 8 is to meaningfully protect the online privacy of Canadians in today’s overwhelmingly digital world, it must protect their IP addresses.

A. Legal Framework

[29] Section 8 of the Charter guarantees “the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure”. Its principal object is the protection of privacy, or the individual’s “right to be left alone” (R. v. Edwards, [1996] 1 S.C.R. 128, at para. 67). Personal privacy is vital to individual dignity, autonomy, and personal growth (R. v. Jones, 2017 SCC 60, [2017] 2 S.C.R. 696, at para. 38). Its protection is a basic prerequisite to the flourishing of a free and healthy democracy.

[30] To establish a breach of s. 8, a claimant must show there was a search or seizure, and that the search or seizure was unreasonable. Only the first requirement — whether the request for the IP addresses was a search — is at issue here.

[31] A search occurs where the state invades a reasonable expectation of privacy. An expectation of privacy is reasonable where the public’s interest in being left alone by the government outweighs the government’s interest in intruding on the individual’s privacy to advance its goals, notably those of law enforcement (Hunter, at pp. 159-60). Courts analyze an expectation of privacy by considering many interrelated but often competing factors, which can be grouped together under four categories: (1) the subject matter of the search; (2) the claimant’s interest in the subject matter; (3) the claimant’s subjective expectation of privacy; and (4) whether the subjective expectation of privacy was objectively reasonable (Spencer, at para. 18, citing Tessling, at para. 32).

[32] This case is about informational privacy, or “the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others” (Tessling, at para. 23, quoting A. F. Westin, Privacy and Freedom (1970), at p. 7). In other words, this aspect of privacy is concerned with “informational self-determination” (Jones, at para. 39).

B. The Subject Matter of the Search

[34] Considering the subject matter of the alleged search allows the court to identify the privacy interests at issue (Spencer, at para. 22). A guiding question in defining the subject matter of the alleged search is “what were the police really after?” (Marakah, at para. 15, citing R. v. Ward, 2012 ONCA 660, 112 O.R. (3d) 321, at para. 67). A court must take a holistic view of the subject matter of the search. The approach must not be mechanical, and it must reflect technological reality (Spencer, at paras. 26 and 31; Marakah, at para. 17).

[35] Here, the appellant asks us to adopt the dissenting judge’s characterization of the subject matter. What the police were really after, he says, was “to connect an internet activity to a specific person. Obtaining an IP address was an essential step in identifying the internet user responsible for specific internet activity” (A.F., at para. 37).

[38] This Court has never described the constitutional right to privacy according to the state’s declared intention, or according to one particular use of the information. Rather, we have consistently taken a broad and functional approach to the subject matter of the search, “examining the connection between the police investigative technique and the privacy interest at stake” (Spencer, at para. 26). The subject matter is defined not only in terms of the information itself, but also “the tendency of information sought to support inferences in relation to other personal information” (para. 31). In Marakah, for example, the issue was whether the sender of a text message has a reasonable expectation of privacy in that text message on the recipient’s device. Writing for the majority, McLachlin C.J. determined that the subject matter of the search was not the recipient’s telephone, or even the text message itself, but an “electronic conversation” including “any inferences about associations and activities that can be drawn from that information” (para. 20).

[41]…Police were not “really after” IP addresses in the abstract. As “a collection of numbers”, an IP address is of no interest to police. Rather, police were after the information an IP address tends to reveal about a specific Internet user including their online activity and, ultimately, their identity “as the source, possessor or user of that information” (Spencer, at para. 47). As the identifier of Internet-connected activity originating at a specific location, an IP address is a powerful tool that allows the state — with or without another warrant — to collect a user’s Internet activity over the time period a particular IP address is linked to that source. Thus, as in Reeves, an IP address provided the state with the means through which to draw immediate and direct inferences about the user behind specific Internet activity. The information inferred from a device’s Internet activity can be deeply personal, including linking that activity to a particular user’s identity (see Spencer, at para. 47).

[42] This description takes a broad and functional view of the subject matter. By “properly avoid[ing] a mechanical approach that defines the subject matter in terms of physical acts, spaces, or modalities of [informational] transmission”, it “reflects the technological reality” (Marakah, at para. 17). This description does not extend the shield of Charter protection to every investigatory step. Instead, it affirms that investigative techniques that reveal seemingly innocuous information must still be examined in connection with the privacy interest at stake (Spencer, at para. 26)….

[43] Thus, the subject matter of this alleged search is an IP address as the key to obtaining more information about a particular Internet user including their online activity and, ultimately, their identity as the source of that information. Here, police sought to obtain that information through a production order as contemplated by Spencer. But, as the expert report states, a Spencer warrant is not the only way an IP address can reveal intimate details of an Internet user’s lifestyle and personal choices. Online activity associated to the IP address may itself betray highly personal information without the safeguards of judicial pre-authorization. I turn to that issue next.

C. Was the Expectation of Privacy Reasonable?

[45] Courts must make this determination in the totality of the circumstances. While there is no definitive list of factors (Cole, at para. 45), courts have often focussed on the claimant’s control over the subject matter, the place of the search, and the private nature of the subject matter (see, e.g., Marakah, at para. 24).

Control Over the Subject Matter

[46] In the informational privacy context, the claimant’s control over the subject matter is not determinative (Reeves, at para. 38). The self-determination at the heart of informational privacy means that individuals “may choose to divulge certain information for a limited purpose, or to a limited class of persons, and nonetheless retain a reasonable expectation of privacy” (Jones, at para. 39). Anonymity is a particularly important conception of privacy when it comes to the Internet (Spencer, at para. 45, citing Westin, at p. 32).

[48]…As we said in Jones, “the only way to retain control over the subject matter of the search vis-à-vis the service provider was to make no use of its services at all. That choice is not a meaningful one. . . . Canadians are not required to become digital recluses in order to maintain some semblance of privacy in their lives” (para. 45).

The Place of the Search

[49]… As this Court recently remarked, “online spaces are qualitatively different” from physical spaces (R. v. Ramelson, 2022 SCC 44, at para. 49 (emphasis in original)).

[50]…The information the Internet harbours can reveal much more than information subject to the limits of physical space (see Vu, at paras. 44 and 47). Therefore, the lack of physical intrusion highlighted by the trial judge tells us little about the reasonableness of an expectation of privacy.

The Private Nature of the Subject Matter

[51] Section 8 seeks “to protect a biographical core of personal information which individuals in a free and democratic society would wish to maintain and control from dissemination to the state” (Plant, at p. 293). The “biographical core” is not limited to identity, but “include[s] information which tends to reveal intimate details of the lifestyle and personal choices of the individual” (p. 293).

[52] Section 8’s emphasis on information which individuals “would wish to maintain and control from dissemination to the state” means that a reasonable expectation of privacy is assessed normatively rather than simply descriptively (Spencer, at para. 27, quoting Plant, at p. 293). The normative approach has an aspirational quality. “The question is whether the privacy claim must ‘be recognized as beyond state intrusion absent constitutional justification if Canadian society is to remain a free, democratic and open society’” (Reeves, at para. 28, quoting Ward, at para. 87)….

….This analysis is inevitably “laden with value judgments which are made from the independent perspective of the reasonable and informed person who is concerned about the long-term consequences of government action for the protection of privacy” (R. v. Patrick, 2009 SCC 17, [2009] 1 S.C.R. 579, at para. 14).

[53] Thus, a reasonable expectation of privacy, as s. 8’s operative component, cannot be assessed according to only one particular use of the evidence. Nor can its reach be determined according to the police’s specific intention in seeking the information. Rather, the purpose of s. 8, appreciated normatively, requires that we ask what information the subject matter of the search tends to reveal. Because this analysis seeks to determine “whether people generally have a privacy interest” in the subject matter of the state’s search, we consider not only the information that police seek to uncover in a particular case, but all the information that the subject matter may tend to uncover (Patrick, at para. 32).

[54] This principle is especially clear where there is a search of digital information. Computers are different….

…. Indeed, “it is difficult to imagine a more intrusive invasion of privacy” than searches concerning an individual’s use of the Internet (R. v. Morelli, 2010 SCC 8, [2010] 1 S.C.R. 253, at para. 105).

[56] Similarly, in Reeves, the severity of the privacy concerns arising from the seizure of a computer was unaffected by the police’s specific intention to search the computer for child pornography. Rather, these concerns stemmed from “the personal or confidential nature of the data that is preserved and potentially available to police through the seizure of the computer” (para. 33 (emphasis added), citing Marakah, at para. 32). The Constitution should protect against the seizure of a computer because, in doing so, police “obtained the means through which to access [highly private] information” (Reeves, at para. 34).

[57] The police’s specific intention to restrict the use of information in a particular case — no matter how well-intentioned — is thus irrelevant to s. 8. The “reasonable expectation of privacy” analysis revolves around the potential of a particular subject matter to reveal an individual’s biographical core to the state, not whether the IP addresses revealed information about the appellant on these facts….

[58]…. And, as the expert evidence describes, an IP address is attached to all online activity; it is a fundamental building block to all Internet use. This social context of the digital world is necessary to a functional approach in defining the privacy interest afforded under the Charter to the information that could be revealed by an IP address.

[60] The Crown suggests that an IP address is useless without a Spencer warrant. Respectfully, I cannot agree. First, as the link that connects specific Internet activity to a specific location, an IP address may betray deeply personal information, even before police try to link the address to the user’s identity. Second, activity associated with the IP address can be correlated with other online activity associated with that address available to the state — with particularly concerning consequences when coupled with access to third-party-held information. Finally, an IP address can set the state on a trail of Internet activity that leads directly to a user’s identity, even without a Spencer warrant. The instances when an IP address may betray biographical core information are not all captured by Spencer. In light of these three points, which I elaborate below, access to IP addresses without judicial pre-authorization poses intense privacy risks, and IP addresses attract a reasonable expectation of privacy.

[61] First, the activity associated with the IP address can itself be deeply revealing, even before any attempt to determine identity. Here, the activity was a series of financial transactions through an online intermediary, Moneris. Linked to financial intermediaries like Moneris or PayPal, an IP address can reveal all of a user’s transactions on that intermediary over the period the IP address was assigned to them….

[62] These purchases may “broadcas[t] a wealth of personal information capable of revealing personal and core biographical information about the [purchaser]” (Marakah, at para. 33), from the restaurants they frequent, the destinations they visit, the hobbies they enjoy, to the health supplements they use. Internet users may even have “an acute privacy interest in the fact of their electronic [purchases]”, especially as our marketplaces rapidly migrate online (para. 33 (emphasis in original)).

[63] Other online activities can reveal information that goes directly to a user’s biographical core. Websites offering dating services or adult pornography can give the state a depiction of the user’s sexual preferences. An Internet user’s history on medical, political, or other similar online chatrooms can reveal their health concerns or political views. If an IP address is not protected, this information is freely available to the state without the protection of the Charter whether or not it relates to the investigation of a particular crime.

[65] Without the protection of s. 8, nothing prevents the state from pre-emptively collecting IP addresses and comparing that user’s IP address against their database. Further, and significantly, the scope of information that an IP address can reveal is enormous if correlated against information held by a third party. Cases suggest that third parties provide this information without being asked….

[67] A great deal of online activity is performed anonymously (Spencer, at para. 48; Ward, at para. 75). People behave differently online than they do in person (Ramelson, at para. 5). “Some online locations, like search engines, allow people to explore notions that they would be loath to air in public; others, like some forms of social media, allow users to dissimulate behind veneers of their choosing” (para. 46). We would not want the social media profiles we linger on to become the knowledge of the state. Nor would we want the intimately private version of ourselves revealed by the collection of key terms we have recently entered into a search engine to spill over into the offline world. Those who use the Internet should be entitled to expect that the state does not access this information without a proper constitutional basis.

[68] Finally, link by link, an IP address can set the state on a trail of anonymous Internet activity that leads directly to a user’s identity. The expert uses the example of an IP address that logs onto a particular social media profile or email account containing information from which the user’s identity can be inferred, such as their name. From there, the user’s identity is but a short inference away. It is not an answer to say — as Crown counsel does — that a Spencer warrant is required if the IP address is sought in relation to information that can unveil the identity of the Internet user….

Does the Balance Weigh in Favour of a Reasonable Expectation of Privacy?

[72] Here, the intensely private nature of the information an IP address may betray strongly suggests that the public’s interest in being left alone should prevail over the government’s interest in advancing its law enforcement goals. I will elaborate.

[74] Even “information that may at first blush appear mundane and outside of the biographical core may be profoundly revealing when situated in context with other data points” (N. Hasan et al., Search and Seizure (2021), at p. 59). Aggregation “creates synergies….

[75] Not only does the Internet keep an accurate permanent record, it has concentrated this mass of data in the hands of third parties, investing these third parties with immense informational power….

[76] The Internet has not only allowed private corporations to track their users, but also to build profiles of their users filled with information the users never knew they were revealing. “Browsing logs, for example, may provide detailed information about users’ interests. Search engines may gather records of users’ search terms. Advertisers may track their users across networks of websites, gathering an overview of their interests and concerns” (Spencer, at para. 46). Commentators have even suggested that companies can use the data they collect to infer “what you are going to purchase, the kind of person you are going to get into a relationship with, whether you will be good at a new job, how long you will stay at that job, and whether you’ll get sick” (H. Matsumi, “Predictions and Privacy: Should There Be Rules About Using Personal Data to Forecast the Future?” (2017), 48 Cumb. L. Rev. 149, at p. 149).

[78] By concentrating this mass of information with private third parties and granting them the tools to aggregate and dissect that data, the Internet has essentially altered the topography of privacy under the Charter. It has added a third party to the constitutional ecosystem, making the horizontal relationship between the individual and the state tripartite. Though third parties are not themselves subject to s. 8, they “mediat[e] a relationship which is directly governed by the Charter — that between the defendant and police” (A. Slane, “Privacy and Civic Duty in R v Ward: The Right to Online Anonymity and the Charter-Compliant Scope of Voluntary Cooperation with Police Requests” (2013), 39 Queen’s L.J. 301, at p. 311).

[80] Even if the IP address does not itself reveal the user’s identity, the prospect and ease of a Spencer warrant means that the user’s identity can later be revealed, not only in relation to the potentially criminal Internet activity in question, but in relation to all the information that can be inferred from the user’s Internet activity. As the appellant argues, comparing the IP address of an identified user with other online activities “shatters [online] anonymity completely” (A.F., at para. 45).

[84]… Police should have the investigative tools to deal with crime that is committed and facilitated online.

[85] In my view, however, requiring that police obtain prior judicial authorization before obtaining an IP address is not an onerous investigative step, and it would not unduly interfere with law enforcement’s ability to deal with this crime. Where the IP address, or the subscriber information, is sufficiently linked to the commission of a crime, judicial authorization is readily available and adds little to the information police must already provide for a Spencer production order. For example, under s. 487.015(1) of the Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, a production order for information relating to a specified transmission of a communication is available if there are reasonable grounds to suspect that an offence has been or will be committed….

[86] On balance, the burden imposed on the state by recognizing a reasonable expectation of privacy in IP addresses pales compared to the substantial privacy concerns implicated in this case….

[87] …. In a democratic society, it is “inconceivable that the state should have unrestricted discretion to target whomever it wishes for surreptitious [digital] surveillance” (R. v. Wong, [1990] 3 S.C.R. 36, at p. 47).

[88] Judicial oversight in respect of an IP address is the way to accomplish s. 8’s goal of preventing infringements on privacy. Since Hunter, we have held that s. 8 seeks to prevent breaches of privacy, not to condemn or condone breaches after the fact based on the state’s use of that information. Privacy, once breached, cannot be restored.

[89] Finally, judicial oversight removes the decision to disclose information — and how much to disclose — from private corporations and returns it to the purview of the Charter. The increase in state power occasioned by the Internet is thus offset by a broad, purposive approach to s. 8 that meets our “new social, political and historical realities” (Hunter, at p. 155). To leave it to the private sector to decide whether to provide police with information that may betray our most intimate selves strikes an unacceptable blow to s. 8. To leave the protection of the Charter to the next intended step in the investigation is insufficient. As I have explained, the next step might be too late.

[90] Thus, viewed normatively, s. 8 of the Charter ought to extend a reasonable expectation of privacy to IP addresses. They provide the state with the means through which to obtain information of a deeply personal nature about a specific Internet user and, ultimately, their identity whether or not another warrant is required….

….Recognizing a reasonable expectation of privacy in IP addresses would ensure that the veil of privacy all Canadians expect when they access the Internet is only lifted when an independent judicial officer is satisfied that providing this information to the state will serve a legitimate law enforcement purpose.

[91] In my view, the reasonable and informed person concerned about the long-term consequences of government action for the protection of privacy would conclude that IP addresses should attract a reasonable expectation of privacy. Extending s. 8’s reach to IP addresses protects the first “digital breadcrumb” and therefore obscures the trail of an Internet user’s journey through the cyberspace.

V. Disposition

[92] I would find the request by the state for an IP address is a search under s. 8 of the Charter. I would allow the appeal, set aside the conviction, and order a new trial.

R v Gill, 2024 BCCA 63

[February 26, 2024] S.8 Charter – Overseizure, Failure to file Report to Justice [Reasons by Groberman J.A. with Griffin and DeWitt-Van Oosten JJ.A. concurring]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Searches pursuant to a warrant do not provide police with carte blanche to seize whatever they find. Police can only seize those things which are explicitly mentioned in the warrant or things that criminal to possess and are located in plain view while searched for items listed in the warrant. This case turned on the interpretation of what “cell phone” (singular) meant in a warrant. Police seized everyone’s cell phone in the residence. Trial judge found this was an over seizure and the Court of Appeal agreed (although in their interpretation, this was because this authorized police to search for the target’s cell phone(s), but not other people found in the home during the search.

The police in this case also engaged in the failure to file a report to a justice for an extended period of time. This failure meant not only were the cell phones seized unlawfully to begin with, but their retention by police was unlawful for years in this case. An exclusion of evidence was upheld by the Court of Appeal.

Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Mr. Justice Groberman:

[1] The Crown appeals from Mr. Gill’s acquittal on one count of second degree murder and one count of attempted murder. It seeks to have the matters remitted to the Supreme Court for a new trial, contending that the trial judge erred in excluding evidence. For reasons that follow, I would dismiss the appeal.

Overview of the Voir Dire Rulings Leading to the Exclusion of Evidence

[2] The verdicts came after the trial judge ruled that the seizure and continued detention of three cellphones and a surveillance system by the police violated the accused’s right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure under s. 8 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms [the Charter]. The judge considered that admitting critical evidence from those seized items would bring the administration of justice into disrepute. He therefore excluded the evidence under s. 24(2) of the Charter. Following that ruling, the Crown consented to a re-election by the accused to be tried by judge alone and called no evidence. Mr. Gill was, accordingly, found not guilty of the charges.

[3] There were three voir dires leading up to the judge’s ruling. In the first (2020 BCSC 2030), the judge found that the police had seized items — several cellphones and a home surveillance system — that were not specifically mentioned in the search warrant. He considered that those items were not authorized to be seized under the provisions of the Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, and found that the seizure violated s. 8 of the Charter.

[4] In the second voir dire (2021 BCSC 152) the judge considered the failure of the police to obtain an extension when they elected to hold the seized items beyond the period authorized by the initial order. The judge found that the unauthorized detention was also a violation of s. 8 of the Charter.

[5] In the third voir dire (2021 BCSC 377), the judge considered whether the violations of s. 8 should result in the exclusion of evidence. After considering the factors set out in R. v. Grant, 2009 SCC 32, he found that the evidence should be excluded.

The Search Warrant

[17] The information to obtain the search warrant for the residence did not mention a surveillance system (indeed, the presence of the system was probably not known to police when the information was sworn). While the information indicated that it was being sworn in support of a warrant to search the house for, among other things, Mr. Gill’s cellphone, the affidavit did not expressly indicate what relevance the phone might have to the investigation. Presumably, the deponent considered it obvious that a cellphone might contain a record of calls made and received around the time of the shooting, and the contents of any text messages that were exchanged concerning the events. In addition, if the cellphone had been with the shooter at the time of the killing, the phone’s International Mobile Equipment Identity (“IMEI”) number and the number of the installed Subscriber Identity Module (“SIM card”) might be useful in establishing his presence at the murder scene.

[18] In any event, the police were successful in obtaining a search warrant that specifically authorized the police to seize “Samandeep GILL’s cellular telephone”. No other cellphones were mentioned in the warrant.

The Search

[20] The home was in a disordered state. Belongings of different people were found together in several of the rooms, and belongings of particular individuals were found in more than one room. According to the police, the disorder rendered them incapable of determining which resident resided in which of the five bedrooms in the house.

[21] The police seized all cellphones found in the house, a total of nine devices (six of which did not contain SIM cards).

[24] During the search, the police noticed security cameras, and located and seized a home security system manufactured by a company known as “SVAT” (the “SVAT device”).

Events After the Search was Conducted

[25] On May 19, 2011, four days after the search concluded, the police complied with ss. 489.1(1)(b) and 489.1(3) of the Criminal Code by filing a report in Form 5.2 setting out the items seized from the residence. On May 24, they applied under s. 490(1)(b) for an order allowing them to detain the seized items, and a justice granted the order on May 25. Section 490(2) of the Criminal Code prohibits the detention of items for more than three months unless an application is made for continued detention, or criminal proceedings are commenced.

[30] Despite the progress made in the investigation, it appears to have been put on hold. There is no real explanation for that, apart from a suggestion that it was a very busy time for IHIT, and there were other priorities.

[32] In 2016, the file was transferred to the RCMP Unsolved Homicide Unit, but that unit did not immediately take any steps in respect of the seized items. In January 2018, a without notice application was made to authorize further detention of the cellphones and the SVAT device, and a two-year extension was granted. In argument, the Crown acknowledged that any extension would be without prejudice to Mr. Gill’s right to argue that the continuing detention of the devices from August 2011 until early 2018 had been unauthorized.

[33] On February 28, 2018, the police obtained an order to examine the iPhone. To their surprise, they found that it contained an audio recording of the shooting. The recording is one and three-quarter minutes in length. It includes the voices of two men (Mr. Gill’s voice was identified by his brother-in-law) and a screaming sound that appears to be from a woman. Several gunshots are heard. It is not clear how the recording came to exist, but the Crown theory was that the accused had both the iPhone and a Blackberry with him at the time of the shooting, and pocket dialled the iPhone from the Blackberry.

[34] The audio recording was crucial to the case, as it identified the accused as the person involved in the shooting. The SVAT data was also important, as it showed comings and goings from the home that were consistent with the iPhone’s transfers from one cell tower to another.

First Voir Dire Ruling (2020 BCSC 2030) (“Over-seizure Ruling”)

[37] The law is clear that a seizure, other than one conducted under a search warrant, is presumptively unreasonable. To make evidentiary use of items seized in such a seizure, the Crown must ordinarily show, among other things, that the search was authorized by law: Hunter v. Southam Inc., [1984] 2 S.C.R. 145.

[38] The parties are agreed that, in this case, the only legal bases on which the seizure of the items might be justified are those set out in s. 489(1)(c) of the Criminal Code:

Seizure of things not specified

489(1) Every person who executes a warrant may seize, in addition to the things mentioned in the warrant, anything that the person believes on reasonable grounds

(c) will afford evidence in respect of an offence against this or any other Act of Parliament.

[39] In the judge’s view, none of the seized cellphones could be said to have been “mentioned in the warrant”. He therefore analysed the issue of whether the police believed that the seized phones would afford evidence in respect of the offence, and, if so, whether that belief was based on reasonable grounds.

[41] The judge appears to have placed considerable weight on the fact that the word “telephone” in the warrant was singular. I am not fully convinced that the use of the word “telephone” rather than “telephones” was of significance. The rationale for including Mr. Gill’s cellphone in the warrant was that it was anticipated that a cellphone that he used and carried would contain important evidence. That rationale would have applied equally to any cellphone he used and carried, even if he had multiple cellphones. Neither the police nor the justice who granted the warrant appear to have turned their minds to the possibility that more than one cellphone might conform to the description in the warrant.

[42] While it is not necessary to answer the question on this appeal, I would be inclined to think that, in this situation, any cellphone that fit within the description in the warrant could properly have been seized under it, and if more than one such device was found, the seizure of all such devices would have been acceptable.

[43] The real problem with the seizure here, then, was not that it included more than one cellphone. The major problem—which was also recognized by the judge— was that the police did not, in seizing cellphones, confine themselves to devices that belonged to Mr. Gill. Instead, they seized every cellphone located in the house. They candidly admitted that they did not know which of the cellphones they seized belonged to Mr. Gill, and they made only cursory inquiries and conducted virtually no investigations to gain such knowledge.

[44] The judge considered that the police are not entitled, in executing a search warrant, to cast their net so widely. That is a sensible approach. The warrant was very specific in authorizing the police to seize “Samandeep Gill’s cellular telephone” (Emphasis added). It must have been obvious to the police and to the justice who issued the warrant that there was a strong likelihood that other residents of the house would also have cellphones. The limitation of the warrant to Mr. Gill’s cellphone was, therefore, significant. It was not open to the police to argue that the cellphones they seized were “mentioned in the warrant”, because they took no steps to ascertain whether that was the case.

[45] To justify the seizure of the cellphones, then, the police were required to rely on s. 489(1)(c) of the Criminal Code. They had to show that they believed that the seized items would afford evidence in respect of an offence, and that the belief was based on objectively reasonable grounds.

[46] Those same criteria applied to the SVAT device, which clearly was not mentioned in the warrant.

[48] The judge was not impressed with the evidence provided by the file coordinator. He did not accept her suggestion that she had “no way to know” who the phones belonged to, or who used what room. He found that proposition not to be credible. He also considered that the file coordinator was defensive in giving her evidence, and that aspects of her testimony were unreliable and not credible:

[32] Though I do not attribute the … testimonial shortcomings to any conscious desire to mislead the court, it seems that the Officer fell victim to what was described by Hill J. in R v. Cook, [2008] O.J. No. 4765 (S.C.) at para. 45 as “the natural, but distorting, product of hindsight reflection on justification for the seizure”.

[49] The judge concluded that the file coordinator did not have the subjective belief necessary to satisfy s. 489(1)(c) of the Criminal Code:

[47] The Officer explicitly stated in her testimony that she had no idea whether any of the individual cell phones belonged to the accused. With respect, the Crown’s argument that an inability to discern the ownership of a given phone is different from an inability to discern if it could afford evidence regarding an offence is not convincing. One wonders what evidence of the shooting could be expected on reasonable and probable grounds to show up on a phone belonging to an individual other than the accused.

[48] As such, I find that the Officer’s admission that she had no idea who any of the phones belonged to indicates that she did not subjectively believe she had reasonable and probable grounds to expect any phone she seized to afford evidence in respect of the offence. Her evidence suggests she believed merely in the possibility that each phone might provide evidence, falling below the “credibly-based probability” standard. In fact, her evidence suggests that she may have mistakenly believed that she was warranted to seize multiple phones in the first place.

[50] The judge found that, as the officer had no idea which cellphone or phones belonged to the accused, she could not subjectively believe that any particular phone would provide evidence in respect of the offence.

[51] The judge’s findings on subjective belief were based on his assessment of credibility and reliability and on findings of fact. As such, they are entitled to deference. I am not persuaded that this Court should interfere with them. It appears that, in respect of each cellphone seized, the police had no more than a mere suspicion that there was a possibility that it would afford evidence of an offence.

[58] In the circumstances of this case, he considered that there was an insufficient basis to conclude that any one of the cellphones would afford evidence of an offence. I would not disturb that finding. While it may have been that, with only a few more inquiries or observations, the police could have obtained sufficient information to meet the objective test in respect of the iPhone, they did not do so. In determining the objective reasonableness of a belief, the proper focus is on what the police did, based on what they knew at the time of the seizure, and not on what information they could have acquired: R. v. Glendinning, 2019 BCCA 365 at para. 24.

[59] In deferring to the judge’s findings on reasonable grounds, I do not suggest that there is a general principle that a seizure of a group of items is inappropriate where the items cannot be readily differentiated and only one (or some) of the individual items are likely to yield evidence. A decision as to whether, in such a situation, the seizure of the group of items is reasonable will depend on the totality of the circumstances, as assessed by the judge: see, for example, R. v. Robertson, 2019 BCCA 116 at para. 23–29; R. v. Sipes, 2011 BCSC 1763 at paras. 300–307. The conclusions reached by the judge in this case were plainly shaped by the evidence on the voir dire and, importantly, his credibility findings.

[60] With respect to the SVAT device seizure, the judge rejected the idea that the police had a subjective belief that the surveillance system would provide relevant evidence. He noted that the police did not know whether the system was operational, and that they did not articulate a basis for a belief that it would afford evidence.

[61] On this appeal, the Crown accepts that the police lacked a subjective belief that the device would afford evidence of an offence. On that basis, it concedes that the seizure violated s. 8.

[63] Because I would not interfere with the judge’s findings that neither the subjective nor objective tests in s. 489(1)(c) of the Criminal Code were met for the seizure of the cellphones, I would not interfere with his determination that their seizure violated Mr. Gill’s rights under s. 8 of the Charter. Similarly, the Crown’s concession that the police lacked a subjective belief that the SVAT device would afford evidence of an offence, which concession appears to me to be well-founded, means that its seizure also violated s. 8 of the Charter.

Second Voir Dire Ruling (2021 BCSC 152) (“Over-holding Ruling”)

[65] The Crown accepted that the police retention of the cellphones and SVAT device beyond August 14, 2011 was contrary to s. 490 of the Criminal Code. The application in January 2018 to authorize continued retention of the cellphones did not make their detention for more than six years prior to that time lawful.

[66] The Crown also accepted that the violation of s. 490 was deliberate. The evidence supporting that concession is overwhelming. Several years before the seizure in this case, IHIT officers had been directed by its senior management not to seek extensions of detention orders after the initial three-month authorization expired. They considered that seeking extensions would provide suspects with sensitive information as to the status of investigations. This concern subsisted until, several years later, the courts interpreted the Criminal Code provisions as allowing extension applications to be made without notice and in camera.

[67] In 2007, two senior Crown counsel advised IHIT that it could face legal consequences for failures to abide by the requirements of s. 490 of the Criminal Code. In 2009, a third senior counsel reiterated that advice. Later on, an RCMP lawyer provided a similar warning. Nonetheless, IHIT continued to follow the practice of ignoring the legal requirement to seek an extension.

[70] The judge rejected that argument in the second voir dire. He began by citing R. v. Colarusso, [1994] 1 S.C.R. 20 at 63 for the proposition that a seizure does not end with the taking of items, but rather continues for as long as the items remain in police detention.

[71] While recognizing that merely holding onto cellphones and a surveillance device was not an intrusion of privacy of the same sort or degree as would have resulted from a search of their contents, the judge considered that privacy interests were still at stake, citing from R. v. Reeves, 2018 SCC 56:

[33] … Although a seizure of a computer may be less intrusive than a search of its contents, both engage important privacy interests when the purpose of the seizure is to gain access to the data on the computer. Privacy includes “control over, access to and use of information” (Spencer [R. v. Spencer, 2014 SCC 43], at para. 40). Thus, the personal or confidential nature of the data that is preserved and potentially available to police through the seizure of the computer is relevant in determining whether the claimant has a reasonable expectation of privacy in it (Marakah [R. v. Marakah, 2017 SCC 59], at para. 32).

[72] He then referred to the decision of this Court in R. v. Craig, 2016 BCCA 154, holding that the Criminal Code regime for the handling of seized items after the original seizure engages s. 8 of the Charter:

[181] The Charter protects against unreasonable search or seizure. In my view, a seizure does not end with the picking up of things. The requirement for a return to a justice is the ongoing judicial supervision of things seized— both under a warrant, pursuant to a warrantless search, and pursuant to a common law search: Backhouse [R. v. Backhouse (2005), 194 C.C.C. (3d) 1 (Ont. C.A.)]. This is the only public record of what was in fact seized, whether the items were named in the warrant, whether they were seized as found in plain view, and what was seized outside of a warrant. As noted, there can be a significant invasion of privacy after the picking up of the items—including DNA testing, forensic testing, copying and other examinations. Thus, the privacy interests are continuing.

[182] I agree with the approach taken by the Ontario Court of Appeal in Garcia-Machado [R. v. Garcia-Machado, 2015 ONCA 569] and Butters [R. v. Butters, 2015 ONCA 783] that the failure to strictly comply with the statutory provisions of the Criminal Code will result in a Charter breach where the accused had an ongoing residual privacy interest and rendered the continuing detention unreasonable. I also agree that the circumstances are best left for an analysis under s. 24(2) of the Charter.

[74] I see no error in the trial judge’s approach. Case law makes it clear that the retention of seized items, even without further examination of them, can constitute a violation of s. 8 of the Charter….

[78] I agree with Bennett J.A.’s observation at para. 182 of Craig that “the failure to … comply with the statutory provisions of the Criminal Code will result in a Charter breach where the accused had an ongoing residual privacy interest … [and] that the circumstances are best left for an analysis under s. 24(2) of the Charter.”

[79] Accordingly, I would not interfere with the judge’s decision on the second voir dire.

[103] The judge took a reasonable approach to the issue. Cellphones typically contain large stores of private information, and the ability to control and access that information is Charter-protected. The judge fully understood what was at stake in this case and made no reversible errors in his application of the law.

[104] The Crown, here, concedes that the flagrant and apparently deliberate breach of the law by police officers was egregious. When that characterization is combined with a finding that the breach had a serious effect on Charter-protected rights, the case for excluding evidence is very strong, indeed.

[105] As made clear by the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Tim, 2022 SCC 12 at para. 82, a wilful or reckless disregard of a Charter right falls at the “more serious end” of the culpability scale for Charter-infringing conduct. It was open to the trial judge to conclude that admitting the cellphones and SVAT device into evidence would bring the administration of justice into disrepute.

[106] The Court must not, in these circumstances interfere with the judge’s discretionary decision to exclude evidence, even in the face of extremely serious offences that had tragic human consequences.

Conclusion

[107] I would dismiss the appeal.

R v Slapkauskas, 2024 ONCA 154

[February 7, 2024] Sentencing: Pre-Trial Custody in a Hospital [Fairburn A.C.J.O., Rouleau and Trotter JJ.A.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: A short authority for the proposition that pre-trial custody at a hospital counts at 1.5 to 1 like all other pre-trial custody.

[1] The appellant pled guilty to manslaughter and flight from police. He received a global sentence of 14 years, less credit of 929 days (calculated at 1.5:1 for time detained) collectively in provincial jails, and 427 days (calculated at 1:1 for time detained) in Providence Continuing Care Hospital. For the time detained in Providence Continuing Care, the sentencing judge gave very brief reasons for departing from R. v. Summers, 2014 SCC 26, [2014] 1 S.C.R. 575, credit as follows:

PCC is a modern hospital in which, by the offender’s own admission, he is receiving treatment for his substance abuse issues and his mental health issues.

[2] Amicus argues that the trial judge erred by failing to grant Summers credit at 1.5:1 for the time detained at Providence. Amicus says that this fails to acknowledge the quantitative rationale for crediting time detained in presentence custody at 1.5:1 to align it with earned remission after being sentenced. This sets up a concerning situation where those who face mental health and/or substance abuse challenges can, in effect, end up serving longer sentences simply because of where they are detained prior to sentence.

[3] The Crown respondent acknowledges that the sentencing judge gave insufficient reasons to justify the departure from enhanced credit in this case. We agree.

[4] While we note that this court has previously addressed a similar issue in R. v. J.W., 2023 ONCA 552, leave to appeal to S.C.C. requested, 40956, 1 J.W. is factually distinct from this case. We see no basis on the factual record of this case that would justify not giving credit at 1.5:1 for the time the appellant was detained at Providence Continuing Care Hospital.

[5] We thank both counsel for their very helpful submissions. Leave to appeal sentence is granted. The appeal is allowed and the appellant will be credited an additional 214 days toward his sentence.

Our lawyers have been litigating criminal trials and appeals for over 16 years in courtrooms throughout Canada. We can be of assistance to your practice. Whether you are looking for an appeal referral or some help with a complex written argument, our firm may be able to help. Our firm provides the following services available to other lawyers for referrals or contract work:

- Criminal Appeals

- Complex Criminal Litigation

- Ghostwriting Criminal Legal Briefs

Please review the rest of the website to see if our services are right for you.