This week’s top three summaries: R v Willier, 2025 ABKB 370: Ares v Venner #Expert Evidence, R v Zabihullah, 2025 SKCA 64: 11(b) particular #complexity, R v Moazami, 2025 BCCA 189: trial #aggravating sentence

R v Willier, 2025 ABKB 370

[June 18, 2025] The Common Law Business Records Exception to Hearsay [Justice N. Whitling]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Limits of the Business Records Exception in Criminal Cases

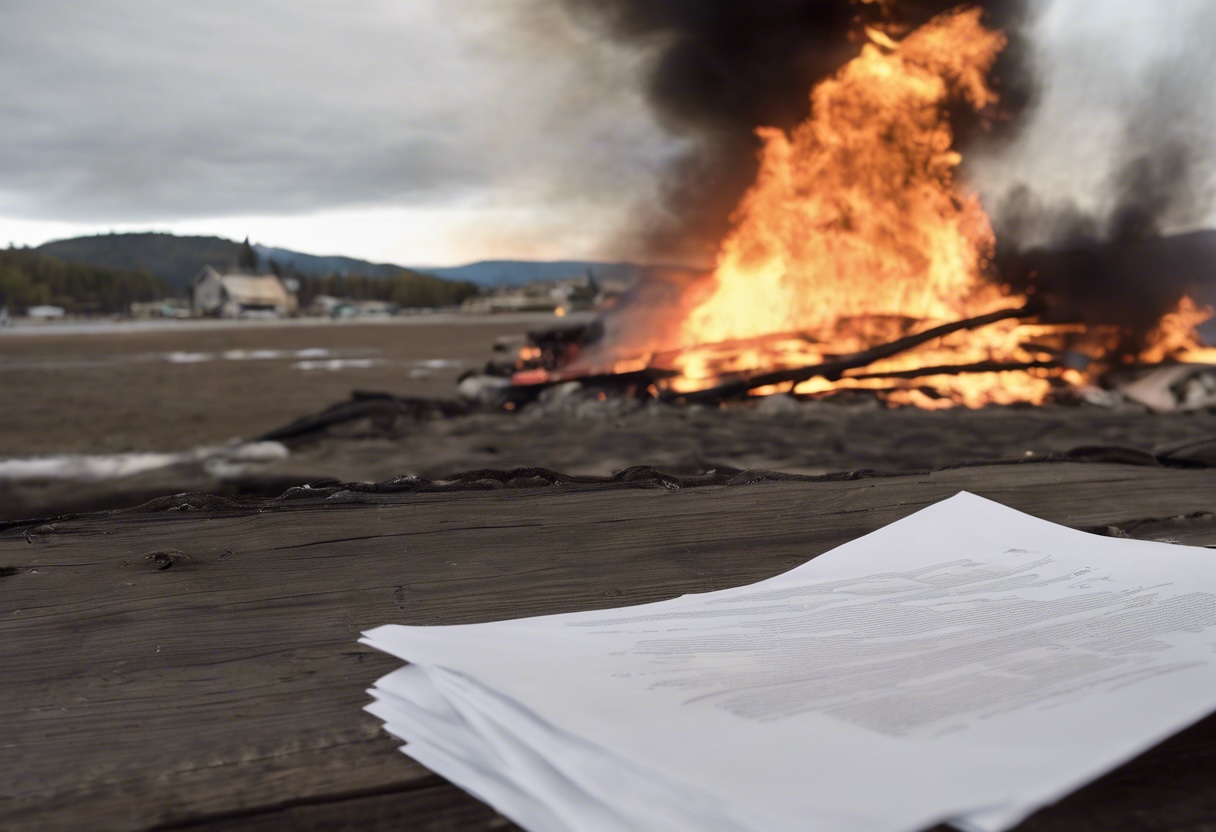

Ares v. Venner established a common law exception allowing business records to be admitted as hearsay without notice to the defence. However, many business records in criminal cases contain embedded expert opinions—such as those from doctors, nurses, or investigators.

In this case, the Court addressed the admissibility of expert opinion evidence within business records. It held that a true opinion, given by someone within their specialized expertise, cannot fall within the business records exception. Specifically, the opinions of a fire investigator regarding the fire’s point of origin, ignition source, and whether it was deliberately set were not admissible under the common law rule.

This reinforces that expert opinions must meet the stricter requirements of admissibility for expert evidence, including qualification and necessity, and cannot be admitted merely because they appear in a business record.

R v Zabihullah, 2025 SKCA 64

[June 4, 2025] Charter 11(b): Particular Complexity [Leurer C.J.S., Caldwell J.A. and Bardai J.A.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Delay Not Excused by Legal Uncertainty Alone

While Jordan allows for delays beyond the presumptive ceiling if a case is particularly complex, the Supreme Court made clear that even a typical murder trial would not necessarily qualify.

In this case, involving aggravated sexual assault and some legal uncertainty surrounding the constitutionality of ss. 278.92(1), 278.92(2)(b), and 278.94(2) (governing defence-held records in sexual offence trials), the Court found no exceptional complexity justifying delay.

There was no expert evidence or other features that would elevate the case’s complexity. The Crown failed to meet its burden to show an exceptional circumstance, and the delay beyond the Jordan ceiling was not justified.

[1] The Crown appeals an order made by a Court of King’s Bench judge staying charges against Mohammad Zabihullah because of a violation of his right to be tried within a reasonable time, as guaranteed by s. 11(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms: R v Zabihullah (21 December 2023) Regina, CRM-RG-00360-2018 (Sask KB) [Delay Decision].

[3] Mr. Zabihullah was charged under an information sworn on May 7, 2018, in connection with offences alleged to have occurred, in one instance, between July 29 and 30, 2017, and on May 5, 2018, in another. After a preliminary inquiry held on October 10, 2018, Mr. Zabihullah was committed to stand trial on charges of assault, contrary to s. 266 of the Criminal Code, and aggravated sexual assault, contrary to s. 273. The trial was initially scheduled to take place on October 15 and 16, 2019 [First Trial Dates]. Due to a number of factors, Mr. Zabihullah’s trial was postponed many times and eventually set down for April 8–12, 2024.

[5] Under that structure, the judge found that the total delay between the laying of the information to the anticipated end of trial was 2,168 days (see Delay Decision at para 64). He subtracted from this total defence delay, which he determined to be 109 days, bringing the net delay to 2,059 days (see paras 72–73). After an extensive analysis, he identified three exceptional circumstances that had caused additional delay, being an adjournment due to the death of a member of Crown counsel’s family, the COVID-19 pandemic and the withdrawal by Mr. Zabihullah of a guilty plea in relation to one offence, which had caused the First Trial Dates to be vacated (see paras 74–109). Based on these events, the judge deducted 853 days from the net delay, with the result that the remaining delay in the case amounted to 1,206 days or the equivalent of 40 months and 6 days (see para 110). Finally, the judge rejected the Crown’s argument that some time should be factored into the overall delay analysis to account for the fact that this was a complex case (see paras 111–117). Taking all of this into consideration, the judge found that Mr. Zabihullah’s right to be tried within a reasonable time, as guaranteed by s. 11(b) of the Charter, had been violated, and he imposed a stay of proceedings with respect to the two charges before him.

[6] The Crown takes no issue with the judge’s general approach. Instead, in its factum it focuses on two errors he allegedly made.

[7] The Crown’s first argument….

….We see no reason to explore the intricacies of this submission because, even if the Crown’s argument had merit, accounting for the judge’s alleged error would still leave the time to trial above the presumptive ceiling set in Jordan by over four months….

[8] The Crown’s second argument is that the judge erred in his consideration of the complexity of the case. Its submission is that the judge “erred in law by imposing the incorrect legal standard in the case complexity determination”. The Crown emphasizes that the test is reasonableness, not perfection, referring to the statement given in Jordan that the Crown “is not required to show that the steps it took were ultimately successful — rather, just that it took reasonable steps in an attempt to avoid the delay” (at para 70)….

[9] Unlike defence delay and discrete events, “case complexity requires a qualitative, not quantitative, assessment” (R v Cody, 2017 SCC 31 at para 64, [2017] 1 SCR 659). The Supreme Court has also emphasised that a determination as to whether a case’s complexity justifies a matter taking longer than the presumptive ceiling “falls well within the expertise of a trial judge” (Cody at para 64, referring to Jordan at para 79).

[10] A particularly complex case is one that, “because of the nature of the evidence or the nature of the issues, require[s] an inordinate amount of trial or preparation time” (Jordan at para 77, emphasis in original, see also Cody at para 64). Here, the judge explained why this case should not be considered to be sufficiently complex to justify exceeding the Jordan presumptive ceiling:

[113] The accused, Mr. Zabihullah, stands charged with one count of common assault, contrary to s. 266, and one count of aggravated sexual assault, contrary to s. 273 of the Criminal Code respectively. As counsel for Mr. Zabihullah quite correctly points out, at para. 100 of her brief, the Supreme Court of Canada, in Jordan, concluded that even a typical murder trial would not qualify as a complex case.

[114] The parties have had the benefit of a preliminary inquiry, and the trial of these allegations is estimated to take only two days; the Indictment lists only the complaint and one police witness, the case does not appear to be document intensive and there is no indication that any expert evidence will be proffered by either party.

[115] Counsel for the accused submits, and in the circumstances, I accept, that the only complicating issue in this case was the uncertainty surrounding the constitutionality of s. 278.92(1), 278.92(2)(b) and 278.94(2) of the Criminal Code.[Emphasis by PJM]

[11] We see no error in this part of the judge’s analysis and therefore can find no error in his bottom-line conclusion that the “present case, considered as a whole, simply does not rise to the threshold of a complex case as contemplated in Jordan” (Delay Decision at para 117).[Emphasis by PJM]

[26] In conclusion, we were unconvinced by the grounds of appeal advanced by the Crown in its factum to intervene in this matter. We were also not prepared to allow the Crown to expand upon those grounds. Thus, we saw no basis to interfere with the judge’s decision to stay the charges against Mr. Zabihullah based on the arguments that were properly brought before us by the Crown. This made it unnecessary for us to consider the arguments advanced by Mr. Zabihullah to the effect that the judge had erred by attributing too much delay to him and to the exceptional circumstances.

[27] We therefore dismissed the Crown’s appeal.