This week’s top three summaries: R v A.S., 2022 SKQB 60: #mistrial for BACA bikers, R v N.G., 2022 ONSC 1875: #credibility & a missing nose, and R v Boakye, 2022 ABPC 72: #defence of property

This week’s top case features a sexual assault trial against a minor. For great general reference on the law related to this area of practice, I recommend the Emond title below. It is available for purchase now for our readership with a 10% discount code provided below. To purchase, simply click on image below.

Prosecuting and Defending Offences Against Children: A Practitioner’s Handbook

By Lisa Joyal, Jennifer Gibson, Lisa Henderson, Emily Lam & David Berg

R v A.S., 2022 SKQB 60

[March 2, 2022] Mistrial for Victim Supporter Interference [Justice Crooks]

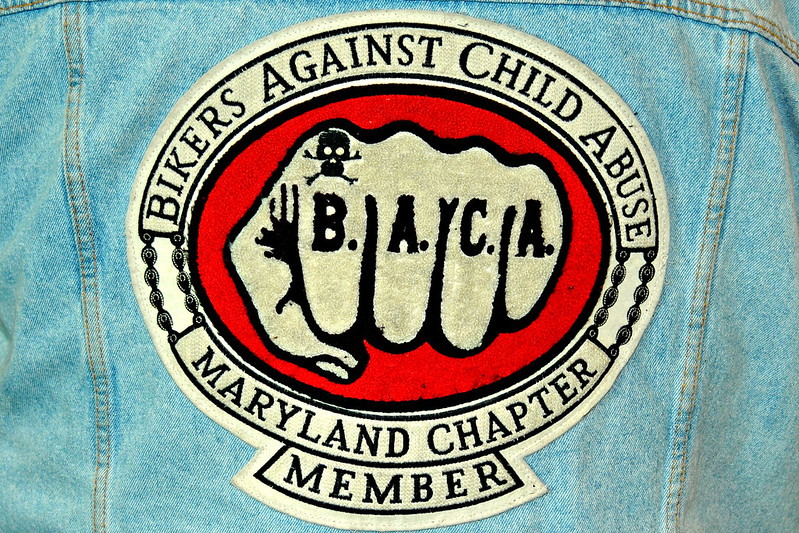

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In the few years preceding the pandemic it became increasingly popular for supporters of alleged victims to attend court proceedings. It has become increasingly common for these supporters to be personally unknown to the complainant and they come with a generalized agenda to support all complainants without regard to the credibility or reliability of their stories. Also, it has become more common for supporters (known and unknown to complainants/alleged victims) to wear outward symbols of support whether it be pins, T-shirts, or in this case biker kit. These outward expressions of support are attempts to wield political pressure in the courtroom and they make judges’ jobs harder because they try to openly influence the result by their mere presence and expression of support by numbers. Here, the pressure crossed the line and resulted in a mistrial when BACA members sat outside the remote courtroom and talked so loud they were heard through the remote CCTV of the complainant within the courtroom.

Overview

[1] Counsel for the defence filed an application for a mistrial. Upon hearing the application for a mistrial, I granted the application with written reasons to follow. These are my written reasons.

[3] Prior to the trial commencing, counsel for the Crown made application pursuant to s. 486.1(1) of the Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, for a support person to be present with the complainant while he testified. That support person was a Victim Witness Specialist. The Crown also applied for the complainant to provide his testimony outside the courtroom pursuant to s. 486.2(1) of the Criminal Code from a location typically referred to as the “soft room”. Counsel for the accused consented to both applications.

[5] The first morning of trial, the complainant began his testimony. In attendance as support for the complainant were members of Bikers Against Child Abuse [BACA]. It is not uncommon for members of BACA to attend court with a child complainant to empower a young witness in providing their testimony. There were four members present in the courtroom while the complainant’s testimony was heard.

[6] After the complainant provided his evidence-in-chief, the Court took a break before returning for cross-examination. During that break, I was advised that while the complainant was testifying, the Local Registrar learned that unknown persons were sitting directly outside the soft room. The Local Registrar attended, and there were two BACA members sitting outside the soft room. The Local Registrar requested these individuals leave that area. They refused to do so, indicating they were entitled to be in that area and remain outside the soft room.

[7] As the complainant’s testimony continued, the Court Clerk advised the Local Registrar that male voices could be heard through the microphone in the soft room, which was amplified within the courtroom. The Local Registrar again attended the soft room with a Sheriff and directed the BACA members to leave, which they did.

[8] When the complainant returned to the soft room with the Victim Witness Specialist after the lunch break, numerous members of BACA attended with the complainant to the soft room and remained there until court resumed.

[9] I, as trial judge, was advised of these events immediately before the court resumed. I immediately advised counsel of these events. Following discussion with the Court and her client, counsel for the accused confirmed their intention to bring an application for a mistrial. The trial was adjourned, and the mistrial application was heard the next morning.

[10] The Court called the Victim Witness Specialist as a witness on the mistrial application in order to ascertain the events that unfolded outside the courtroom. She confirmed that this was the first time she had encountered members of BACA. Her evidence was that between six and eight BACA members attended with the complainant in the soft room, but she believed they were going to observe from the courtroom. When Court resumed, she cleared the BACA members from the soft room, but she did not escort them any further. She was not aware any BACA members intended to remain in the hallway outside the soft room door during the complainant’s testimony and believed they would be observing from the courtroom.

The Use of Testimonial Aids for Vulnerable Witnesses

[13] It is for reasons of maintaining impartiality and ensuring fairness in the trial process that supports such as Victim Services are integral to the work of the Court. It provides a vulnerable witness with a trained support person who understands the expectations of the Court. They are an invaluable resource to the Court and the justice system as a whole – before, during and after a witness’s court appearance.

[14] In situations where a vulnerable witness testifies, the Court has available a location referred to as the “soft room”, which is connected to the courtroom via videoconferencing. The soft room is a safe place for vulnerable witnesses to feel comfortable sharing their testimony to assist the Court in providing a fair and just assessment of the evidence.

[15] In the Saskatoon Court of Queen’s Bench, the soft room is located in a restricted area of the courthouse, with access available only to authorized persons. The restricted area of the courthouse is an area where judges and court staff are able to move freely and provides access to certain areas where the general public would not expect to pass, such as the judge’s private chambers and the courthouse registry.

The Law

[16] Defence counsel tendered for consideration a summary of the law surrounding mistrial applications as set out by Danyliuk J. in van Ooyen v Carruthers, 2018 SKQB 73. Although that case considered a mistrial application in the family law context, the principles are equally applicable to criminal matters:

[8] The essential nature of a mistrial is clearly set out in Linda S. Abrams & Kevin P. McGuinness, Canadian Civil Procedure Law, 2d ed (Markham: LexisNexis, 2010) at para 16.379:

16.379 A mistrial is an invalid trial, caused by some fundamental error or other serious irregularity in the conduct of the trial. When a mistrial is declared, the trial must start again from the beginning. …

The key focus is whether the ability of the party prejudiced by the error or irregularity is of a sufficient scope or degree to prevent that party from presenting his or her case fully, or from securing a fair adjudication on the merits of that case. The declaration of a mistrial is a last resort, and will occur only where the court concludes that no other curative measure will suffice.

…

[11] I was asked to consider a mistrial application in a criminal jury trial in R v Charles, 2015 SKQB 381. At paras. 31 through 33 I reviewed the law and found as follows:

…

[33] From a reading of the case law on mistrials, the following principles emerge:

(a) There is no “one size fits all” test. The particular circumstances of each case must be carefully assessed by the trial judge.

(b) An accused is entitled to a fair trial, not a perfect trial: R v Khan, 2001 SCC 86 at para 72, [2001] 3 SCR 823.

(c) In Khan at para 73, the question is asked as to whether “a well-informed, reasonable person considering the whole of the circumstances … have perceived the trial as being unfair or as appearing to be so.”

(d) Does the precipitating event relate to a central or peripheral issue? Could it affect the verdict?

(e) Is there any defence or Crown conduct that is a factor?

(f) What corrective measures are available that can adequately remedy the problem? Would a mid-trial instruction assist?

(g) “What matters most is the effect of the irregularity on the fairness of the trial and the appearance of fairness”: Khan at para 84.

(h) A mistrial should only be granted as a last resort, in the clearest of cases, and where no other remedy is available: R v Toutissani, 2007 ONCA 773at para 9.

[12] These basic guiding principles overlay mistrial applications, be they in the criminal, civil, or family law context.

Analysis

[18] There can be a fine line between supporting a witness and interfering in the fairness of a proceeding. The reasons for the BACA members remaining outside the soft room are unclear. There were no security concerns brought to the Court’s attention. The accused was in custody, and an officer was present with him in the courtroom.

[20] A “support person” has a clearly defined role through s. 486.1(1) of the Criminal Code, which states:

|

|

|

[21] In my view, this provision specifically requires an application and resulting order permitting one support person to be present and close to the witness while they testify. In making the order, the judge must consider whether this would interfere with the proper administration of justice. In making this assessment, a trial judge is likely to hear from both counsel on the grounds for the request and how this would impact each parties’ respective rights.

[22] The trial judge is the “gatekeeper” in a criminal trial. This is reflected in s. 486.1(1) and s. 486.2(1) of the Criminal Code, where the trial judge must consider whether an order authorizing the use of testimonial aids would interfere with the proper administration of justice.

[23] It cannot be left to a supporter or advocate to take upon themselves responsibility for a witness’s safety or security within the courthouse. These decisions are squarely within the Court’s purview and any concerns should be immediately identified through a Sheriff or Crown counsel, who will then raise any issues with the presiding judge. The security of a witness and their comfort in providing their testimony is always a consideration to the jurists of this Court. However, this is balanced with numerous aspects of trial fairness.

[24] Unfortunately, in these circumstances, this assessment was removed from the Court’s hands by the unilateral actions of the BACA members who remained outside the door of the soft room and carried on conversation during the complainant’s testimony.

[25] Of significant concern to the Court was the conversation occurring outside the soft room while the complainant testified. It is unknown what was said outside the door of the soft room. The Victim Witness Specialist testified that she heard this as mumbling. While the door to the soft room is a solid door with no window or means to communicate visually, the ongoing conversation continuing throughout the complainant’s testimony was loud enough that the members’ voices could be heard through the microphone in the soft room and amplified in the courtroom. I have no doubt the voices were heard by the complainant as he testified. It is unknown what was being discussed, but it could be heard over the speaker in the courtroom while the complainant was testifying.

[26] If disruptive behaviour occurred in the courtroom, such as conduct which had even the potential to influence or distract a witness, it would be stopped immediately either by the presiding judge or by the Sheriff tasked with maintaining order in the courtroom. It may be done on the Court’s own motion or through consultation with counsel or the Sheriff. This is to ensure the integrity of the process and the veracity of a witness’s testimony. It would be unacceptable to allow any influence of a witness while they are testifying, including talking while testimony is being provided or generally distracting witnesses in the proceedings while they are providing testimony.

[28] This is of significant importance in this particular case. The testimony of the complainant was crucial to the Crown’s case. This was not a peripheral witness, but a central witness to the charges against the accused. The complainant was recognized as a vulnerable witness by both counsel and the Court. The testimonial aids offer a supportive environment for vulnerable witnesses to testify, but also must preserve the atmosphere and integrity of the legal process. In effect, the soft room is an extension of the courtroom while the complainant is testifying.

[29] The possibility that there was direct or indirect influence on the complainant’s testimony by the presence of the BACA members both inside the soft room leading to the complainant’s testimony and, more particularly, by carrying on a conversation outside the soft room while the complainant testified cannot be ruled out.

[30] The role and location of the support person is for the Court to determine. It is not for any advocate or supporter to take upon themselves decisions that have the potential to impact the fairness of the trial. In this case, Crown counsel should have been advised of the supporters’ intentions so that the issue could be raised with the Court. It is only through that process that the trial judge can consider the legal principles which may ultimately impact upon the conduct of the trial.

Conclusion

[32] I am mindful that at the centre of this trial and application, there are two participants that will be most impacted. First is the accused, who remains on remand while a second trial is arranged. Second is young [redacted], who will be required to attend court on another day to provide his testimony. This weighed heavily in my considerations.

[34] By proceeding without any input from counsel or the trial judge, these advocates made a unilateral decision which impacted trial fairness. This is why there is an impartial trier of fact who is the gatekeeper of the Court’s processes and mindful of the balance between the needs of witnesses and the rights of the accused. It is simply not feasible when such decisions are made by advocates of one of these parties as their interests weigh heavy on one side over the other.

[35] The presence of advocates outside the soft room was an issue that required judicial consideration. Further, the distraction of the ongoing conversation and the obvious presence of these individuals immediately outside the soft room have the potential for an apprehension of unfairness in the trial process.

[36] In this case, the presence of the BACA members went beyond providing support for the complainant. It became a distraction within the courthouse, interfering with the complainant’s evidence and impacting the accused’s trial fairness.

[37] Here, the members of BACA took it upon themselves to perform the gatekeeper function. They were present in the soft room immediately prior to the complainant’s testimony, with six to eight members in attendance. After being advised that Court was resuming, they made a unilateral decision to remain immediately outside the soft room.

[38] The position of defence counsel is that the impacts of the BACA members’ presence cannot be known. What is known is that the conduct reflects that which would never be permitted in a courtroom. For advocates to be carrying on a conversation immediately outside the room where a key witness is testifying to the extent their voices can be heard through the microphone in that room and refusing to leave when requested by the Local Registrar raises serious concerns around interference with the administration of justice.

[39] In the circumstances of this case, there is a reasonable possibility of prejudice to the accused. As the testimony of the complainant is integral to the Crown’s case, there were no alternative remedies presented which would allow the trial to be saved in a way that is just and fair in the circumstances.

[40] Victim advocates and supports who wish to take on a role beyond observing in the courtroom are well-advised to seek direction from the Court through the prosecutor. It is only through that process trial fairness can be protected.

[41] The defence application for a mistrial is granted.

R v N.G., 2022 ONSC 1875

[March 29, 2022] The Power of a Good Cross-Examination – Reliability/Credibility Acquittal [Conlan J.]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Herein a master class in effective cross-examination by Alan Gold (with a touch of good fortune) led to an acquittal in difficult to believe circumstances. Undisputed facts seemed to suggest that the accused bit off the complainant’s nose. At issue was the reliability and credibility of her account about how this transpired. Remarkably, the good cross-examination here caused a reasonable doubt about the accused’s intent resulting in an acquittal.

Overview

[2] It is alleged that, at his house, in the early morning hours on New Year’s Day 2020, N.G. intentionally bit off the nose of his female partner, A.D., resulting in a gruesome injury to her face, and that he blocked her exit from the residence as she tried to flee for help.

[3] N.G. was tried by this Court, without a jury, via Zoom, over six days in March 2022. Identity, date, and jurisdiction were all admitted by the defence. Further, the injury to A.D. and that it constitutes a wound, maiming, and/or disfigurement, within the meaning of section 268 of the Criminal Code, were not contested by the defence.

[4] There are only two issues to be decided by this Court:

a) did the accused intentionally bite off his partner’s nose; and

b) did the accused actually confine A.D.?

[5] In other words, mens rea is the focus on the aggravated assault charge, and the actus reus itself is the dispute on the forcible confinement allegation.

The Criminal Justice System

[6] In Canada, we do not decide criminal trials by comparing versions of events and picking one. We also do not decide criminal trials on the basis of what is more likely to be true.

[8] What is that burden? It is to meet a standard significantly higher than proof of likely or probable guilt. It is to prove the guilt of the accused beyond a reasonable doubt. Not to a degree of absolute certainty, but to a degree of sureness. The trier of fact must be sure of the guilt of the accused before finding so.

[10] I say most respectfully, lawyers and decision-makers sometimes recite this “formula” in a robotic way, losing sight of its true purpose. The point is that a criminal trial is not over even if the accused is found to be a lying miscreant, to adopt strong language. It could be that, despite a finding that the accused’s evidence is completely incredible and/or unreliable, the rest of the evidence at trial does not rise to the level of proof beyond a reasonable doubt; in that instance an acquittal is mandatory.

What Happened?

[11] According to the alleged victim, what happened was a vicious assault of her in the bathroom, by an angry N.G., after they attended at a bar in downtown Toronto. They were arguing in the bathroom. She threatened to go home. He put his hands down her throat to stop her from breathing and from screaming. She bit down on his hand(s). He looked at her. He then bit off her nose. She was gushing blood and afraid for her life. She ran to escape the house, but he blocked her at the front door. She eventually pushed past him and got out.

[14] According to the accused, there was indeed an argument and violence at the house, after the bar. It culminated in the two of them being in the bathroom. A.D. tried to strike him, again. He yelled something out. That startled her, and she crouched down in the corner of the bathroom. He squatted down next to her. He was telling her it’s okay and rubbing her back. He went to kiss her face. His eyes were closed, and he tried to suck on her upper lip, as that was something that he had done before. He tasted make-up, a “chemically” taste. She turned over her left shoulder and struck him to his lower jaw with her right fist, upper-cut style. There was a lot of blood. He was in shock. He was “zoned-out”. He was just staring at her. Her nose had been bitten off. He went to the kitchen to fetch something that could help like ice from the freezer, but she ran out of the house. He did not try to block her exit in any way.

[15] N.G.’s evidence was exculpatory on both counts. He denied any criminal intent in that the biting of the nose, according to him, was accidental/inadvertent/unintentional. He further denied any blocking of A.D. at the front doorway.

Assessment of the Evidence

[16] I do not believe the evidence of the accused. I have concluded that his evidence is not trustworthy.

[17] First, he did not tell the truth to Froom, and that concerns the Court. We know that A.D. never pulled a knife on him or stabbed him. In fact, he cut his own hand with a knife from the kitchen, and he did that to deceive the police. That concerns the Court as well.

[21] I also have serious reservations about the evidence of A.D. Her evidence is equally untrustworthy. It suffers from both credibility and reliability flaws, and significant ones.

[22] First, she agreed with Mr. Gold in cross-examination at trial that she was inconsistent in her two statements to the police on the issue of her alcohol consumption prior to the incident having occurred in the bathroom. She agreed further that, because she was aware of that contradiction, she told the Crown in direct examination at trial that she could not remember how much she drank. Why she would not have been more honest and direct with the police in simply admitting that, right away, makes me uncomfortable.

[23] Second, she was, prior to the trial, and closer to the time of the incident, much more uncertain about what happened in the bathroom. That makes me wonder why she is so much clearer about it now, long afterwards. She told the police, who asked a very simple question, “do you know what happened to your nose”, “I genuinely didn’t know what happened”; “I was drunk at that point”, she said (trial Exhibit 10). Those were her own words. She was drunk, and she did not know what happened.

[24] Third, it is very clear from trial Exhibit 12, the video clip from the parking garage of the accused and A.D. just after they had left the bar in downtown Toronto, that she was extremely drunk. Without him steadying her, she could barely walk or stand straight. That gross level of intoxication makes me question the reliability of her memory of what happened in the bathroom not long afterwards.

[25] Fourth, there is no question that A.D. lied at the preliminary inquiry. She lied when she told Mr. Gold in cross-examination that she was sure that she did not text or contact the accused in any way after the incident. In fact, at the preliminary inquiry, during the lunch break that occurred in the course of cross-examination, A.D. asked the Crown what she should do if she “lied” about something in her evidence. Of course, a deliberate lie under oath or affirmation is a very serious matter. And there is no question that A.D. knows the difference between a lie and a mistake, and that what happened at the preliminary inquiry was a lie, because she told Mr. Gold in cross-examination at trial that she understands that a lie is an intentional falsehood. [Emphasis by PJM]

[26] Remarkably, despite what happened at the preliminary inquiry, at trial, in direct examination by the Crown, the complainant again failed or refused to state the whole truth. She admitted only that she had texted the accused after the incident. In fact, she also telephoned him and spoke for a very, very long time, even though he did not talk back to her. The full recorded call was played in Court – trial Exhibit 13A, with all of its lengthy and incessant ramblings on the part of A.D. She was highly embarrassed by the call, and that was clear to me as I watched her on the screen as the recording was played.

[27] How A.D. could not remember that very lengthy telephone call when she gave her evidence in direct examination at trial, I do not know, especially given what happened at the preliminary inquiry. I am left with the inescapable conclusion that she deliberately omitted any mention of the call when she was asked by the Crown in direct examination at trial about any contact that she had with the accused post-incident. That is concerning to this Court. [Emphasis by PJM]

[28] A.D. also admitted in cross-examination at trial that, when she made that telephone call, she knew that the accused was on bail with a condition that he not speak with her. A person who does that, in my opinion, is not showing proper respect for the administration of justice. Again, I am concerned by that.

[29] Finally, A.D. has more at stake here than the average alleged victim. She has an outstanding lawsuit against the accused and his father, for a massive amount of money, and it goes without saying that she has an interest in providing evidence to this Court that does not impair the chances of success of that civil action.

[30] In summary, this Court cannot trust the evidence of A.D. about what happened in the bathroom. She is not a credible or reliable witness.

[31] The other evidence at trial that I do accept, such as that of the two police officers, Froom and Garcia-Yepes, makes me quite suspicious of N.G. He lied bald-faced to Froom about the alleged stabbing with the knife. He appeared to be trying to escape out of the backyard when Garcia-Yepes saw him on the fence.

[32] But the totality of the evidence that I do accept does not rise to the level of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. I am definitely not sure that N.G. intentionally bit the nose or face of his partner. I am definitely not sure that he attempted in any way to block her exit from the house.

[33] One of the headings herein, above, asked “what happened on New Year’s Day”. Apart from this lady having sustained a very serious injury to her face, the straight answer is that I do not know.

[34] This Court feels terrible about what happened. I know that A.D. will be hurt by some of my comments about her evidence, and I take no pleasure in that. A.D. suffered an awful injury to her face. Whatever happened that morning, she did nothing to deserve that. This is not an exercise in sympathy, however. It is a criminal trial, with a relatively high standard of proof that is commensurate with the presumption of innocence.

[36] The Crown has not proven the case beyond a reasonable doubt.

[37] N.G. must be acquitted of both charges, and thus the verdict is not guilty on each of the two counts on the Indictment.

R v Boakye, 2022 ABPC 72

[March 29, 2022] Defence of Property [Judge O.A. Shoyele]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Though obviously a much lower level of court, this case represents the opposite end of the spectrum to the SCC’s Khill decision in 2021. While Mr. Khill snuck through his home with a firearm to confront the trespasser rummaging through his car, Mr. Boakye simply asked the unwanted ex-girlfriend to leave his shared residence twice. When she didn’t go, he physically moved her to the door. This case shows a textbook application of the defence of property with a good overview of the law. Of note, the Accused did not testify.

Introduction

[1] Mr. Charles Boakye stands charged with a one-count Information alleging that on or about the 14th day of August, 2021, at or near Edmonton, Alberta, did unlawfully assault Melvina Tamakloe, contrary to section 266 of the Criminal Code of Canada.

Evidence

Melvina Tamakloe

[4] The Complainant testified that she was sitting on a chair, by a dining table in the House, sipping a beverage when the Accused came and asked her, twice, to leave the House without giving any reason for the demand. The Complainant refused; and thereafter, the Accused dragged her out of the chair and started to beat and hit her.

Sebbestina Ebbah

[15] Thereafter, Ms. Ebbah reiterated that she did not see the Accused “punch” the Complainant; instead, she observed the Accused “push” the Complainant after tapping her on the shoulder and asking her to leave.

Reginald Acquah

[22] He recalled doing the dishes when the Complainant came around to the apartment. He saw the Accused come downstairs to ask the Complainant to leave, and went back upstairs. The Accused came back to ask the Complainant to leave and insisted that should happen immediately that second time around. The Complainant refused, so the Accused forced her out.

[23] In describing how the Accused forced the Complainant out, the witness said the Accused pushed the Complainant out of the barstool or chair she was sitting on, and dragged her out. Mr. Acquah recollected that the Complainant was holding a phone that fell off her hands with the push. She then picked it up and made a call. The whole incident, in his estimation, lasted “a little over ten minutes.” Thereafter, the Complainant stepped out of the House voluntarily.

The Law

[27] Section 35 of the Criminal Code provides:

(1) A person is not guilty of an offence if

(a) they either believe on reasonable grounds that they are in peaceable possession of property or are acting under the authority of, or lawfully assisting, a person whom they believe on reasonable grounds is in peaceable possession of property;

(b) they believe on reasonable grounds that another person

(i) is about to enter, is entering or has entered the property without being entitled by law to do so,

(ii) is about to take the property, is doing so or has just done so, or

(iii) is about to damage or destroy the property, or make it inoperative, or is doing so;

(c) the act that constitutes the offence is committed for the purpose of

(i) preventing the other person from entering the property, or removing that person from the property, or

(ii) preventing the other person from taking, damaging or destroying the property or from making it inoperative, or retaking the property from that person; and

(d) the act committed is reasonable in the circumstances.

[28] Judge S Schiefner in R v Chaboyer, 2020 SKPC 6 at paras 41-45 wrote:

[41] Defence of property has long been recognized as a limited defence in Canada. This defence is codified in s. 35 of the Criminal Code. The defence applies to a wide range of offences and to any type of property. The defence is triggered when a person subjectively believes that the actions of another person are threatening the peaceable possession of the subject’s property. See: Cormier v R, 2017 NBCA 10 at paras 37 & 47, 348 CCC (3d) 97 [Cormier].

[42] Section 35 provides that a person is not guilty of an [offence] (including in this case – assault) if four essential elements are present: (1) the person must have peaceable possession of property or alternatively they reasonably believe they are entitled to such possession; (2) the person must have a reasonable belief that their property is threatened by trespass, theft or vandalism; (3) the person’s actions must be for the purpose of retaking or preserving that property; (4) the person’s actions must be reasonable under the circumstances. See: Cormier at para 47. See also: [R v Pankiw, 2014 SKQB 381 at para 34].

[43] For the trier of fact, the subject’s belief in their entitlement to peaceable possession in certain property and their perception of a threat to that property is assessed on a subjective basis (from the subject’s perspective). However, the reasonableness of the subject’s response to that threat is measured on an objective basis (what would a reasonable person have done under the circumstances). See: Cormier at para 47.

[44] Much like the defence of self-defence, “reasonableness” is the [principal] filter for the application of the defence of property to justify an action that would otherwise be an offence. Assuming the other elements are present, if the actions of the Accused are objectively reasonable under the circumstances, they are justified at law and the subject is not guilty of the concomitant [offence].

[45] Finally, [the accused person] need not prove the application of this defence. If I find there is an air of reality to the defence arising from the evidence,then s. 35 applies unless the Crown can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that at least one of the elements of the defence was not present. See: R v Caswell,2013 SKPC 114, 421 Sask R 312.

[29] It is worthy of emphatical mention that s 35(1)(c)(i) of the Criminal Code includes an alternative purpose to retaking or preserving a property as potential justifications for the commission of an offence in relation to one’s property. That sub-section indicates that a person is not guilty of an offence if the act that constitutes the offence is committed for the purpose of removing that person – i.e., a trespasser, being a person who has entered the property without being entitled by law to do so – from the property.

Analysis

[43] Thus, while the written statement provided by Ms. Ebbah to the police that the Accused punched the Complainant was inconsistent with her evidence at trial, the totality of the evidence accepted by this Court in the trial leads to the conclusion that the Accused neither punched nor choked the Complainant.

[44] For the purpose of the assault charge against the Accused, I accept the evidence of Mr. Acquah – who incidentally let the Complainant into the House. Mr. Acquah calmly and unflinchingly testified that the Accused pushed the Complainant out of the chair she was sitting on by the barstool and dragged her out. As a result of the force applied by the Accused, the Complainant’s phone that fell off her hands with the push; following which she picked up the phone and called the police. Mr. Acquah struck me as a credible, objective and reliable witness.

[47] The extant jurisprudence confirms that the use of minimal force without consent is sufficient to establish assault: R v Jobidon, 1991 CanLII 77 (SCC), [1991] 2 SCR 714; R v Dawydiuk, 2010 BCCA 162; and R v Burden at paras 16-18.

[48] Based on the aforementioned legal principle, I conclude that the whole of the evidence before me supports the finding that the Accused deployed a level of force that meets the requirement for the commission of an assault offence, under the Criminal Code. That evidence confirms that, without the Complainant’s consent, the Accused intentionally pushed and dragged the Complainant, as described earlier.

[49] Nevertheless, the Accused in the present case is not denying the use of force against the Complainant. Rather, he argues reasonable force was used for the purpose of removing the Complainant, who had become a trespasser at that point, from the subject property.

[53] She submits that while the evidence of the Crown’s witnesses in this case support some air of reality to the defence of property, the Accused did not act in defence of property: R v Hummel, 2011 ABPC 311 at para 43, where the Court indicated that if someone has permission of the lawful occupier to enter the premises, they are said to be an invitee or a licensee.

[55] He posits that the “air of reality” is based on the evidence before this Court that the Accused was a lawful occupant of the House at the relevant time. His name was on the lease, he paid rent, and shared the House with other roommates. The evidence before the Court also confirms that both the Accused and the Complainant had broken up and there was lingering animosity between them.

[58] The evidence before this Court confirms that the Accused was one of the legal co- occupants of the property involved in this case, while the Complainant was a guest or visitor who had not been expressly invited by any of the occupants of the House. The Accused claims his action was executed for the purpose of removing the Complainant from his shared property after she refused to leave the premises.

[59] In the foregoing circumstances, coupled with Crown’s concession, I conclude that there is an air of reality to the defence of property raised by the Accused in the within matter.

[60] “Should there be an air of reality to the advanced defence, the burden is then upon the Crown to disprove at least one of the elements of the defence beyond a reasonable doubt”: R v Tomlinson, 2014 ONCA 158 at para 51.

Issue III – Has the Crown proved beyond a reasonable doubt that at least one of the elements of the defence of property was not present in this case?

(1) Did the Accused have peaceable possession of property or alternatively reasonably believed he was entitled to such possession?

[68] Consequently, I find that the Accused was a co-renter of the subject property who was recognized on the rental lease; and accordingly, had peaceable possession – or alternatively had grounds to reasonably believe he was entitled to a peaceable possession – of the property at the time of the incident on August 14, 2021.

(2) Did the Accused have a reasonable belief that his property was threatened by trespass?

[69] The Crown submits that by letting the Complainant into the residence shared with the Accused, the Complainant was invited to the home. This act of invitation was further demonstrated, the Crown says, through the offering of a drink to the Complainant.

[78] In any event, even if the Complainant was impliedly invited, as the Crown appears to suggest, that invitation was revoked once the Accused demanded that she should leave. The Complainant would have had a lawful reason to stay if any of the roommates had protested or informed the Accused that she was there at their invitation.

[79] The general legal principle applicable in co-rental scenarios was captured by Redman PCJ, as he then was, in R v Hummel at para 62 as follows:

… [Two] or more persons who jointly occupy a premise are permitted by contract or otherwise to agree to restrict their rights to the use and enjoyment of the property. The occupiers might agree that certain portions of the property may be shared and other portions are not: for example, there can be agreement that each occupier will not invite people into the other’s bedroom, but is free to invite people into other portions of the house. There may even be cases where, by contract or otherwise, the parties agree that one person, for a particular circumstance or over a particular time period, has the unilateral right to invite or to exclude.

See also, R v Cardinal, 2001 ABPC 92, and R v Taylor (2002), 2002 ABPC 54 (CanLII), 315 AR 392.

[81] Although the Complainant’s evidence was that she obtained information on social media that Isaac was having his graduation party, the social media information does not constitute an open invitation to all and any member of the public to attend the graduation party – absent evidence of any lucid language to the contrary.

[82] The evidence before me is clear that the Complainant was not expressly invited by any of the co-residents. Neither could the Complainant have invited herself into somebody else’s home, as she cannot give (or do) what she does not have the legal authority to do (nemo dat quod non habet). The Complainant was not a lawful occupier of the subject Home and as such could not have invited herself into the House by simply sending text message to one of the occupiers that she was on her way to the Premise.

[83] It is noteworthy that in R v Hummel there was an “express invitation” by one of the co- occupants of the property, and the Court in that case went on to consider the related issue of: “whether one legal occupier of a home can revoke an invitation extended by another legal occupier of the home, and as such convert the status of invitee or licensee to a trespasser”: ibid at paras 45, 64.

[89] Further, the Complainant was expressly asked to leave by one of the residents (i.e., the Accused who has a right to the subject shared property and space). Even in other cultural settings where “surprise visit” or “implicit invitation” is countenanced, once the surprise visitor is put on notice that their “invitation” has expired and revoked, the expectation is that they must leave; otherwise, the visitor becomes a trespasser by their refusal to comply with the host’s demand.

[90] A lexicographic source specifically defines “criminal trespass,” inter alia, as a “trespass in which the trespasser remains on the property after being ordered off by a person authorized to do so.”13

[91] Similarly, the Court in R v Hummel at para 43 said:

By [its] simplest definition a trespasser is someone who has entered premises without the permission of the lawful occupier. If they have permission they are said to be an invitee or licensee. However, their status may change. An invitee or licensee may become a trespasser by exceeding the scope of their invitation or by overstaying their welcome: Linden Feldthusen, Canadian Tort Law 8th Ed. p.713.

[Emphasis added].

[93] This apparent neutrality of the co-renting roommates did not confer any right on the Complainant to remain on the co-rented property after one of the co-renters had asked her to leave. The existing residential tenancy legal regime in the Province of Alberta recognizes that the Accused is independently (and equally with the other co-tenants) entitled to a peaceable possession as well as enjoyment of the property including the common, shared space where the assault occurred.

[94] On that basis, the Complainant was required by law to leave when requested to do so by the Accused – who had equal proprietary interest in the leased dwelling House alongside his roommates.

[96] This analysis might have turned out differently if one of the co-renters of the subject House had objected to the Accused’s demand for the Complainant to leave. On this note, it is worthy of mention that unlike the case in R v Hummel – where one of the co-occupants invited her mother and the co-occupant spouse did not want the invited guest in the house – there is no evidence of demonstrable disagreement or conflict in the present case between the Accused and the other occupiers of the subject House that could have been extended or projected to the Complainant. Instead, the disagreement was strictly between the Accused, as a co-occupier of the subject property, and the Complainant, an uninvited guest in the House.

[97] Effectively, an uninvited individual who is on a property becomes a trespasser once the individual has been asked to leave the property by one of the lawful occupiers, absent unequivocal objections from the other lawful occupiers: R v Chaboyer at para 42; R v Hummelat para 43.

(3) Did the Accused act for the purpose of retaking, preserving, or removing the Complainant from the property?

[99] The evidence in this trial demonstrates that Mr. Acquah saw: (i) the Accused asked the Complainant to leave the first time, and the Complainant refused; (ii) the Accused came back the second time to ask the Complainant to leave and insisted that should happen immediately the second time around, and the Complainant still refused; (iii) consequently, the Accused forced the Complainant out by pushing her out of the barstool she was sitting on, and dragging her out.

[102] In this case, the Accused is entitled to preserve the peaceable possession of his proprietary interest; enjoy and preserve his right to privacy in his home – particularly in the circumstances where the Accused and the Complainant were no longer in a cordial relationship – and inclusively remove the Complainant from the property when and where he believes the Complainant has become a trespasser.

[103] On the basis of the evidence accepted in this matter, I conclude that it was after the Complainant refused to leave the property – sequel to two apparently polite demands to leave by the Accused – that the Accused formed the belief on reasonable grounds that it was justifiable for him to act by resorting to the use of force for the purpose of removing the Complainant from the Premise.

(4) Were the Accused’s actions reasonable under the circumstances?

[106] The Defence argues that any physical altercation between the Accused and the Complainant occurred while the Accused was trying to defend himself from the Complainant’s attacks. The Accused’s efforts to politely get the Complainant out of the House failed; and consequently, the Accused tried to get the Complainant out by holding her hands, following which the Complainant started to hit him; while the Accused proceeded to use both hands to restrain her from hitting him.

[108] In essence, the Defence argues, following the altercation the Accused had a clear objective reason to think the Complainant had entered and remained on his property without a lawful basis to do so. He submits that the Accused acted in defence of his property to prevent the Complainant from creating a hostile and uncomfortable environment in his House.

[109] I agree with the Defence’s position that the evidence of the Complainant on the nature of force used on her was incoherent and unclear on the process for her removal by the Accused.

[112] The Complainant’s evidence above is confusing as to whether she was dragged out of the House by the Accused or whether she left the House on her own volition.

[115] A synthesis of the evidence above, leads this Court to find that there was apparently an overlap between the Accused’s action in dragging the Complainant from the barstool towards the entrance of the House and the Complainant’s act of stepping out of the House voluntarily. In essence, the Accused must have suspended the dragging manoeuvre, at some point, in order to permit the Complainant to voluntarily step out of the property. That sequence of occurrence, in my opinion, does not rise to the level of what can be described as excessive force.

[116] Further, the lack of objective evidence of injuries – such as a medical record – from the clinic attended by Complainant or photos of bruises, as well as the fact that she only attended the clinic after close to a week’s delay in order to deal with injuries resulting from the assault suggest that the injuries sustained were not severe. Indeed, the Complainant confirmed in her evidence that the injury sustained “wasn’t serious.”18 The inference that this Court draws from this lack of severity is that the force applied by the Accused to remove the Complainant from the dwelling house was reasonable and not excessive.

[117] The totality of evidence in this case does not support the suggestion that the Accused used excessive force on the Complainant in the process of removing her from the property.

Disposition

[120] Accordingly, the Accused is acquitted.

Prosecuting and Defending Offences Against Children: A Practitioner’s Handbook

By Lisa Joyal, Jennifer Gibson, Lisa Henderson, Emily Lam & David Berg